The COPS Office has agreed to engage with the North Miami (FL) Police Department (NMPD) through the Organizational Assessment program under the Collaborative Reform Initiative continuum of technical assistance services. North Miami is a community of approximately 60,000 residents; as of the beginning of 2024, NMPD has 121 sworn personnel and 34 non-sworn personnel.

One operating principle of the Organizational Assessment program is transparency. This web page is designed to openly communicate the process, progress, and outcomes of our work.

This web page was updated on 9/26/24 and will be periodically updated.

Project Status

Table 1. Status of NMPD recommendations

| STATUS | RECOMMENDATIONS | PERCENT % | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Complete | 0 | 0 |

|

Partially Complete | 0 | 0 |

|

In Progress | 10 | 71 |

|

Not Started | 4 | 29 |

| Total | 14 | 100 |

Table 2. Recommendation status definitions

| STATUS | DEFINITION | |

|---|---|---|

|

Complete | The recommendation has been sufficiently demonstrated to be complete based on the assessment team’s review of submitted materials, observations, and analysis. Ongoing review throughout the engagement will determine whether the recommendation is being sustained and institutionalized within the department. |

|

Partially Complete | The assessment team has determined that additional effort is needed to complete the recommendation. The agency has decided to not pursue additional efforts towards completion. |

|

In Progress | Implementation of the recommendation is currently in progress based on the assessment team’s review of submitted materials, observations, and analysis. |

|

Not Started | The agency has not sufficiently demonstrated progress towards implementation of the recommendation. |

Through the Organizational Assessment program, areas for organizational improvement and reform are addressed by the agency in coordination with subject matter experts continually throughout the engagement to provide timely and ongoing guidance and recommendations while also providing technical assistance to accomplish reforms.

Findings and recommendations listed in the following sections have been developed through a comprehensive assessment and collaboration between the COPS Office, the NMPD, and a multidisciplinary team of experts. The implementation of these recommendations will be monitored and updated throughout the course of the program.

Findings and Recommendations

Focus Area 1: Crime Prevention and Analysis

Finding 1.1. The NMPD is committed to developing and using crime analysis in the agency, but it should be more fully integrated into agency operations and decision-making.

- Crime analysis is a valuable tool for law enforcement agencies as it equips agencies to identify emerging trends, allocate resources, and plan crime prevention and public safety strategies. As a department builds its crime analysis capacity, it should consider several components, including (1) personnel with appropriate skills, knowledge, and abilities to not only conduct crime analysis but also integrate it into agency operations and decision-making; (2) a defined goal and purpose of crime analysis; and (3) appropriate data, technology, tools, and processes to support its ability to conduct and use robust analysis in an efficient and effective manner.

- NMPD leadership recognizes the importance and value of effective crime analysis for daily policing operations. However, much of the one crime analyst’s daily work comprised tabulation of crime statistics for the monthly StatTrax meeting and ad hoc tasks in support of various department needs with fewer opportunities to conduct in-depth analysis of crime or problem trends.

- Compounding the relatively limited analysis is the analyst’s recent departure. Upon learning of the crime analyst’s impending departure, the NMPD immediately began to develop a job posting for the position. The agency partnered with an external expert to review applications and included crime analysts from neighboring agencies in the interview process to ensure the department has sufficient crime analysis expertise to make an informed decision on potential candidates. The new analyst started on July 22, 2024.

With the new analyst onboarding with the agency, the agency will need to consider how to thoughtfully integrate crime analysis into agency operations. Without this critical piece, the NMPD may not maximize the full potential of crime analysis for the agency. The NMPD should also consider hiring more than one crime analyst not only to increase capacity but also to signal to the rest of the department the importance of this function to inform department strategies.

Recommendation 1.1a. Develop a strategic vision and goals for the NMPD crime analysis unit.

Crime analysis can play a critical role in providing a comprehensive approach to crime reduction in an agency. Crime analysts can help integrate crime-fighting efforts with community policing and problem-oriented policing approaches by bridging multiple sources of crime and community data in concise and digestible ways. These functions can play a pivotal role in integrating a data-driven decision-making approach to crime reduction among NMPD command staff, watch commanders, supervisors, and line officers.

As such, the hiring of at least one new crime analyst is an opportunity for the NMPD to redefine the role and responsibilities of that position and the direction of crime analysis in the agency, identifying how crime analysis can contribute to the NMPD’s community safety goals. The NMPD should clearly define how the analyst performs tasks and how they can best provide guidance on addressing crime and problem trends. The NMPD should also include in the strategic vision a discussion of current data and technology used, as well as short- and long-term goals for crime analysis regarding systems, training, and everyday use in North Miami.

NMPD is actively developing a strategic vision for the crime analysis unit. As mentioned, the new crime analyst started in July 2024. In addition, NMPD became a site for the Bureau of Justice Assistance’s Crime Analysis in Residence (CAR) program in the summer of 2024. The CAR program enables police agencies to enhance their crime analysis capacity by integrating sophisticated crime and data analysis practices, products, tools, and information more fully into the daily operations and management of the department’s crime fighting efforts.

NMPD has been actively collaborating with the CRI and CAR teams on how to best leverage resources available to the agency to transform NMPD crime analysis capabilities and integrate crime analysis strategically throughout the organization.

Recommendation 1.1b. As the NMPD builds its crime analysis capabilities, it should identify and provide training and skill development opportunities for crime analysis staff including networking with fellow analysts in neighboring agencies.

The NMPD should determine a strategic vision for crime analysis and identify the skills and competencies the new crime analyst will need to fulfill this vision. If there are any gaps between the NMPD’s needs and the analyst’s skills, the NMPD should consider professional development opportunities to prepare the analyst for the expected tasks needed to succeed in this position. In addition, given that the NMPD has historically only staffed one crime analyst, the NMPD should consider how to network with state and local agencies as well as national organizations such as the International Association of Crime Analysts to engage the department and analyst on crime analysis topics on a regular basis.

The new crime analyst started in July, 2024, and has been getting up-to-speed on the processes and workflows of NMPD. In addition, while NMPD is developing the strategic vision for crime analysis, NMPD has yet to identify and develop the resulting training needs of the crime analyst and the CRI team agrees with this approach. NMPD needs to identify the direction of crime analysis in the agency before developing a training plan for the analyst to achieve those strategic goals.

Recommendation 1.1c. Engage department leadership, officers, and staff on the objectives, functions, and uses of crime analysis to build understanding and practical applications related to day-to-day NMPD operations.

Equally as important as building the capabilities and competencies of the crime analyst is building an understanding among strategic and operational NMPD decision-makers about how crime analysis and related products should inform NMPD policing activities and provide value to the agency as a whole. Officers at all levels should work closely with the analyst to ask and answer questions about the problems in their beats, districts, or investigative areas of focus as well as requesting assistance in identifying emerging crime issues using a data-informed approach. In addition, crime analysis can assist in the development and standardization of internal performance metrics to assess the effectiveness and efficiency of day-to-day operations.

As part of the development of NMPD strategic goals for crime analysis as recommended in 1.1a, the agency will be engaging with all aspects of the organization to understand where and how to best integrate crime analysis. As a part of support for this recommendation through CRI, the Los Angeles, California Police Department hosted NMPD, along with some other agencies, in July 2024 on their implementation of data-driven approaches into everyday police operations. NMPD learned about LAPD’s implementation of the COMPSTAT process, a data-driven approach to policing that relies on crime analysis and daily accountability for police activities. This opportunity provided NMPD with scalable ways to operationalize daily and weekly crime data and trends into proactive police responses.

Recommendation 1.1d. Realign crime analysis in the organizational chart, possibly placing it directly under NMPD executive leadership.

The NMPD’s crime analysis unit is currently situated in Investigations. Crime analysis should play a broader role in the organization including helping drive strategic decision-making, problem solving, investigations, and patrol operations. This role should be reflected in the organizational structure and reporting chain of command.

For example, much of the crime analyst’s work seems to be conducted in isolation from larger agency operations and activities. As the NMPD reimagines the role of crime analysis in the agency, the crime analyst should listen to officer needs, share information and successes, and encourage officers who are already knowledgeable in crime analysis to be “champions” for the use of crime analysis. Officers should also work with analysts on a problem or project to learn about the data, products, and services that crime analysis can provide.

NMPD plans to identify the strategic vision for crime analysis before considering and implementing any changes in the organizational structure and chain of command for the crime analysis unit. This is a thoughtful and measured approach to this recommendation.

Recommendation 1.1e. The NMPD should consider how to support more than one crime analyst in the agency.

Coupled with partnerships with surrounding jurisdictions recommended earlier, a potential second crime analyst (or part time equivalent) could provide increased capacity to address crime analysis issues collaboratively and develop problem solving networking opportunities within the region. Crime analysis is part data science and part problem solving. Crime analysis in the NMPD could benefit from the department’s providing internal and external opportunities for its analysts to collaborate with fellow analysts to identify crime issues in the jurisdiction and review data on internal operations to track progress towards organizational goals and efficiency measures.

In addition, a second analyst could demonstrate the significance placed on this function to the rest of the organization and provide cross-training on all aspects of crime analysis needed by the NMPD to accommodate expected leave by analysts each year.

NMPD recognizes the importance of implementing this recommendation as evidenced by the request for an additional crime analyst position in the latest requested budget to the City. While it is yet to be seen if the position will be funded, NMPD has prioritized making progress on this recommendation.

Finding 2.1. The NMPD does not have a clear agency-wide information technology strategic plan for moving the agency into the future.

The NMPD currently faces operational challenges due to underused or outdated technology. In addition, the NMPD currently lacks a cohesive strategy to guide how and why it pursues certain technologies and how those technologies, in whole, support the department’s overall mission. As a result, the NMPD has a set of technologies with varying levels of function and utility. With the upgraded technology, NMPD will be able to more efficiently serve the community, maintain public safety, and leverage data for effective community-oriented policing now and into the future.

Based on interviews and observations, there are three technology areas whose current capabilities the NMPD needs to examine critically:

- Policing tools. In 2024, the NMPD is in the process of upgrading the computer-aided dispatch (CAD) and records management system (RMS) that have been in place in various iterations since 2008. While these much-needed upgrades will provide additional capabilities to manage policing processes, interact with the community, and support officers in the field with greater mobile capabilities, the NMPD could benefit from additional tools to support other policing operations such as a more robust crime analysis package for the crime analysis unit and case management system for investigations and internal affairs.

Streamlined tools that officers and detectives can readily use in the field and management reporting systems that command staff can use to understand and address crime issues are vital to supporting an efficient police organization. - Organizational processes. A number of NMPD organizational processes could be automated or conducted digitally through technology to improve efficiency in workflows. For example, some agency processes such as equipment or uniform procurement still rely on paper forms and processes for officers to complete. Streamlining processes in areas such as these could provide much-needed efficiencies in workflows and potentially offer time savings to officers.

- Connectivity. Both in the field and at headquarters, NMPD officers face challenges with connectivity to the internet, a vital piece of modern policing. NMPD officers and staff noted limited availability of mobile applications for officers to access and conduct policing business in the field such as crime mapping or video camera access. In addition, universal wireless connectivity is not currently available in NMPD headquarters. The NMPD needs to consider how to address this fundamental issue to ensure officers have the ability to conduct agency expanded and enhanced policing activities to improve response and capabilities of the agency.

While these technological challenges are not unique to the NMPD, as the agency considers many new strategic directions, it is vitally important for the organization to dedicate attention to the technology and other infrastructure that will be needed to realize its goals.

Recommendation 2.1a. Conduct an all-inclusive inventory of all technologies used agency-wide to determine the utility of all technologies and prioritize updates for growth.

This list of technology assets should be all-inclusive (RMS, CAD, body-worn cameras, license plate readers, communications equipment, computers, cameras, and the like). Once compiled, the agency should determine the users and usage of each piece of technology and determine future paths to strengthen utility (e.g.., updates, replacements).

NMPD is in the process of identifying capabilities and technologies needed to better execute the mission of the agency. For example, prior to participation in CRI, NMPD conducted a maturity study with their CAD/RMS vendor to identify challenges with their current systems and what steps would be needed to implement enhanced capabilities such as better mobile access to these systems in the field. NMPD is planning to conduct a comprehensive examination of technologies during their tenure in the CRI program.

However, compounding this particular issue is that the City of North Miami was the target of a cyberattack in early August, 2024. This attack resulted in NMPD being unable to access and use all data systems and databases except e-mail. The City has been methodically working to restore functions and systems but basic police functions have been a significant challenge.

When this issue is resolved and NMPD is fully operational again, this experience is an opportunity to reflect on the vital technology systems in need of transition to cloud settings for universal access regardless of situation as well as technology costs that could be phased out over time.

Recommendation 2.1b. Develop and adopt an organization-wide IT strategy and roadmap to align technology modernization with data-driven decision-making priorities.

The IT strategic plan should directly support the NMPD’s overall goals and objectives and set forth a roadmap for the IT initiatives that are a priority for the agency. The strategic plan should be developed in consultation with the city’s IT department to ensure that fundamental IT needs (e.g., aging hardware and software, security) are considered during the development of the plan and roadmap.

The NMPD should consider the following process for developing such a strategy:

- Identify overarching agency goals and objectives.

- Interview executive and operational stakeholders to understand how each of their functional areas support the agency’s goals and objectives and how technology and data systems integrate with each of their functional areas.

- Review existing IT and related infrastructure to include identifying the state of core IT solutions and infrastructure and identifying challenges posed by current IT solutions or paper-based processes.

- Create a roadmap for a defined period (3–5 years) based on identified priorities and define resource allocation and budget, in conjunction with IT Services, to support these priorities.

- Prioritize the integration of new technologies that could create efficiencies in organizational processes at the officer and supervisor levels.

- Define metrics to determine how progress and outcomes of the IT strategy will be measured.

- Review and update the strategy annually to ensure it remains in line with agency needs and goals.

As the NMPD develops its IT strategic plan, the agency should consider how each of the various technologies can contribute to data-driven decision-making and policing, including understanding and responding to crime and community issues in the city, conducting thoughtful community engagement, and supporting effective and efficient use of available resources to accomplish its mission.

NMPD has started to have discussions across the organization on technology needs and wants for the organization. This needs assessment for the agency is a critical first step in the development of a strategic roadmap for their IT needs.

Focus Area 3. Employee Wellness, Training and Development, and Retention

Finding 3.1. While the NMPD clearly values professionalism in the organization and agency morale appears to be high, the NMPD should provide additional resources to support employee wellness, such as a peer support program.

- The general morale and enthusiasm for improving the agency was evident in every employee the team encountered. The police facility was clean, and the patrol fleet appeared to be in good condition. The personnel encountered were all attired in a modern, professional police uniform, and professional staff members were in appropriate business attire.

- Executive staff, commanders, and supervisors exhibit a level of professionalism in the organization where the chain of command is observed while also giving opportunities for officers to provide their input and perspective, regardless of rank. The collegiality of the cohort of officers interviewed and interacted with was apparent.

- Command personnel related that Chief Cherise Gause had already made a concerted effort to provide advanced leadership training to her team. The Southern Police Institute Command Officer’s Course was referenced as being used and seemed to be appreciated. The five-month course provides an understanding of effective strategies in policing, leadership, and management with a focus on the application and implementation of these strategies in their agencies. The curriculum includes topics such as organizational leadership, problem-solving, evidence-based policing, and policing management in the 21st century. More information on the course is available at https://louisville.edu/spi/courses/codc.

- Training opportunities for line personnel seemed to be considered on an ad hoc basis, and command staff and officers reported that the agency routinely participates in annual in-service training sessions and provides external opportunities for training as budget and staffing levels allow. The main factor limiting access to training was the mandated minimum officers needed for each shift. Line staff reported that these minimums were a barrier to their attending training because of the significant cost of overtime incurred by employees leaving their shifts to attend training. This perceived and fiscal barrier to attending training seemed to disproportionately affect personnel assigned to patrol assignments.

- The NMPD does not currently have a peer support program. This lack is in part due to the size of the agency; NMPD leadership and officers expressed concern that anonymity of an in-house program would be difficult in a department of this size. The agency does currently have a yearly mandatory wellness check-in with a counselor and is currently developing peer supports in partnership with jurisdictions in the area.

Recommendation 3.1a. Identify and incorporate training priorities into NMPD strategic planning efforts.

As Chief Gause and the NMPD develop a strategic plan for the next 3–5 years (mentioned in section 5), it is important to develop an accompanying training schedule that supports the strategic vision of the plan while also being realistic. The NMPD should consider factors such as required training for officers as well as priority training to align officers’ skills with the goals set out by the strategic plan.

Some agencies develop a yearly training plan that incorporates all of the requirements for officers while simultaneously providing a summary of areas of emphasis for training over a 3- or 5-year time period such as de-escalation, implicit bias, or community problem solving. This schedule helps ensure that officers, over a defined period of time, receive comprehensive training on important topics in policing while also covering required operational and tactical training requirements.

NMPD plans to identify the training needs in tandem with developing the strategic plan for the agency (mentioned in section 5).

Recommendation 3.1b. Identify opportunities for partnership with other agencies on peer support programs that could be anonymous.

The NMPD should continue to find ways to support officers through these programs. The NMPD has been examining external programs such as Cop2Cop, which connects current officers with former officers through a 24-hour hotline, as well as potential partnerships within the region.

The COPS Office has numerous resources for agencies as they consider officer wellness programs. For example, the COPS Office commissioned case studies on officer mental health and wellness programs in agencies across the country and published them in a report titled Law Enforcement Mental Health and Wellness Programs: Eleven Case Studies. This publication examines wellness programs developed and implemented by agencies of different sizes, including the context of their agency, how they approached officer wellness, and insights for agencies considering how to implement similar programs.

In addition, the COPS Office released a guide on a similar topic titled Implementing Peer Support Services in Small and Rural Law Enforcement Agencies. This guide provides a roadmap for small police agencies implementing or enhancing peer support services. It highlights promising practices and provides brief case studies of peer support programs. Topics include establishing trust and buy-in; identifying, training, and supporting team members and leaders; confidentiality; local and regional partnerships; and evaluation metrics.

More information and resources are available at the COPS Office's Law Enforcement Mental Health and Wellness Act Program resource page and in the Community Policing Dispatch article “Peer Support for Officer Wellness.”

As mentioned in finding 3.1, NMPD has already started developing ways to support officers through partnerships across the greater-Miami area including peer support. NMPD should continue to cultivate these opportunities for the organization to enhance the experience and support for officers. In process, training and certifications for 3 peer support officers.

Focus Area 4. Resource Analysis and Strategic Planning

Finding 4.1. The NMPD provides a full complement of public safety services to North Miami including patrol; investigations; and many community policing functions, community service programs, and other specialized units. However, this functional diversity sometimes comes at the expense of a sustainable staffing model for the agency that balances effectively deploying patrol officers during shifts and times with high call-for-service volumes with fielding these specialized units.

- The City of North Miami is located in northeast Miami-Dade County and is a part of the Miami metropolitan area of South Florida with almost 60,000 residents per the 2022 census. The city is approximately 10 square miles.

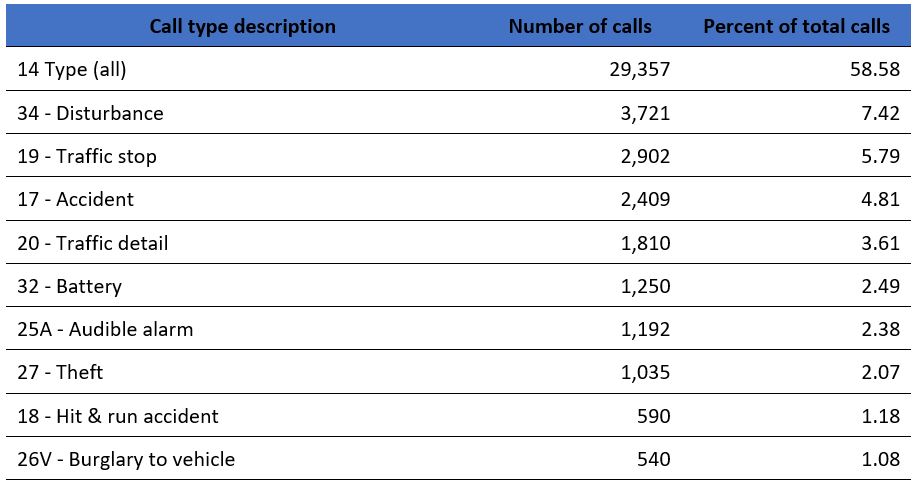

- To support public safety in North Miami, the NMPD as of the beginning of 2024 had 121 sworn personnel with 90 officers, 17 sergeants, 6 commanders, 5 majors, 2 assistant chiefs, and 1 chief. In addition, the NMPD has 36 civilian support personnel in the agency. Based on preliminary analysis of NMPD calls for service from 2023 and review of StatTrax presentations, the NMPD responds to between 50,000 and 60,000 calls for service (CFS) per year, with almost 60 percent of these as “code 14” officer-initiated CFS.

-

NMPD’s “code 14” calls comprise business checks, directed hot spot patrols, and investigative follow-ups. After accounting for “code 14,” other top CFS include traffic-related calls, disturbances, and theft/burglary (table 2).

Table 2. NMPD Top 10 CFS in 2023

Source: NMPD-provided CFS data. -

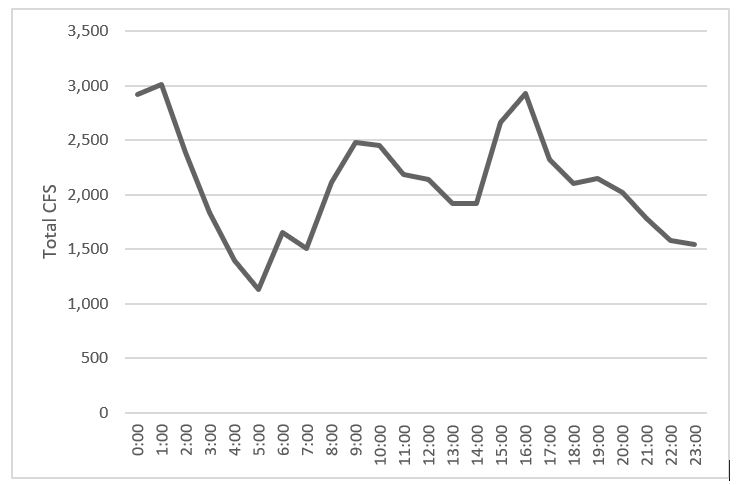

In addition, a majority of CFS (not including “code 14”) come during the afternoon shift (figure 1, 2:30 p.m. – 12:30 a.m. each day), when the NMPD is responding to an average of between one and two more calls per hour than on the other shifts (between 4–5 calls per hour vs. 3–4 per hour).

Figure 1. CFS by time of day, 2023

Source: NMPD-provided CFS data. -

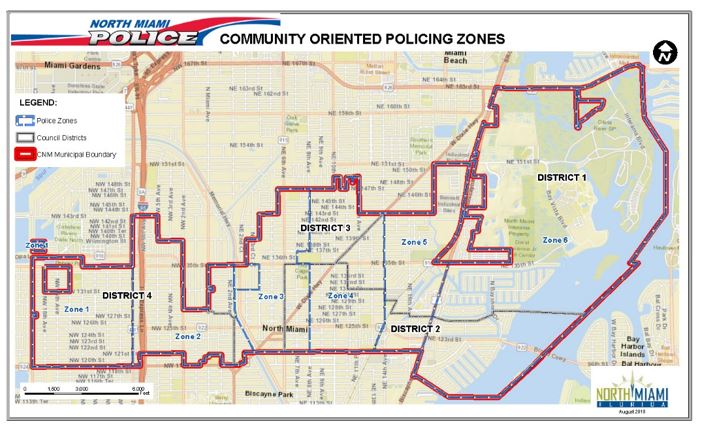

Operationally, the NMPD divides the city into six zones, with zone one beginning at the westernmost boundary of the jurisdiction and zone six ending at the easternmost boundary (figure 2). At any given time, the NMPD has eight officers on patrol in the city. This includes essentially one officer in each of the six zones, one roaming officer, and one officer staffing the desk at NMPD headquarters. As a result, seven officers are actively patrolling six different police districts in the jurisdiction with two officers typically patrolling District 1 and 4 at any given time.

Figure 2. NMPD community-oriented policing zones and council districts

Source: NMPD-provided graphic - Adequate staffing of patrol is a critical component and the backbone of an effective policing model to address public safety issues. A challenge with the NMPD’s staffing model is that in the event of multiple calls for service requiring response for one or more officers, the NMPD’s ability to respond to additional calls or conduct proactive policing activities such as welfare or business checks, community interactions, or directed policing activities suffers.

-

- To ensure appropriate support for North Miami and its communities, NMPD ensures they always have adequate staffing for patrol. However, compounding this staffing issue is that NMPD uses mandatory shifts from specialized units to cover gaps in patrol needs for a particular day or shift to meet this goal. Seniority plays a factor in drafting and less tenured officers in specialized units have the least number of years in the agency do get drafted to serve in patrol shifts on a regular basis.

For example, officers in specialized units are routinely required to work patrol shifts in addition to their regular duties. The result of this approach is that the responsibilities and duties of specialized assignments suffer. This is particularly noticeable in the investigations unit as the unit is unable to work assigned cases on a regular basis resulting in delays in investigations. This also effects the tasks and duties of other units such as COPS, marine, mounted, etc. This staffing model is unsustainable. While patrol needs to continue to be a priority for the agency, this approach is potentially contributing to burnout among patrol officers in specialized units as well as contributing to inconsistent tasking and services from specialized units. - For context, with six months left in the fiscal year in 2024, NMPD was on track to spend more than double the allocated amount in overtime expenses, with patrol accounting for approximately 45 percent of this total. The need to use overtime at this pace illustrates the NMPD’s unsustainable staffing approach.

- The NMPD has numerous specialized units for an agency of its size, including a special weapons and tactics (SWAT) team, a K-9 unit, a marine unit, a mounted unit, community-oriented policing services (COPS) officers, crime suppression officers, a drone unit, and traffic safety officers. These specialized units often support the activities of patrol officers, such as the COPS unit regularly conducting welfare checks and interactions with local businesses.

- Some of these units’ ability to contribute to the mission of the agency is limited because of how the NMPD staffs and deploys officers to them. For example, the marine and mounted horse units typically only deploy with a single officer at a time. This limits officers’ ability to conduct certain enforcement activities such as apprehension or arrest to ensure the safety of the officer while also being attentive to safety of the horse or operations of the boat.

- In addition, specialized units need additional time and resources to adequately staff and maintain facilities such as stables and marina storage and to undergo specialized training. The City of North Miami’s approved budget for the NMPD includes specific allocations for many of these specialized units.

- Despite these challenges and based on interviews, these specialized units offer NMPD officers valuable professional opportunities and experiences compared to similarly sized agencies in the region as well as salary increases for specialized unit assignments. Officers noted their desire to identify specialized units they wanted to pursue early in their tenure with the agency. As the NMPD continues to examine the role these specialized units play in the agency’s long-term goals and mission, it will be important to balance that role with the benefits specialized units provide to the agency and the officers that staff them.

- In the next two to five years, the City of North Miami is expected to experience significant growth in the population of residents and regular jobs in the area. This growth is expected primarily because of a University of Miami medical center being built in North Miami by 2025 and numerous high-rise condominium complexes in active construction. The NMPD must consider how this influx of new residents into the area will impact staffing needs into the future as well as policing operations such as response to calls for service and traffic safety.

Recommendation 4.1a. The NMPD should examine its current and future patrol needs based on reliable data and metrics including allocated and unallocated time for officers. The NMPD should also examine CFS workload by beat, time of day, and crime or call type to align shift needs with staffing.

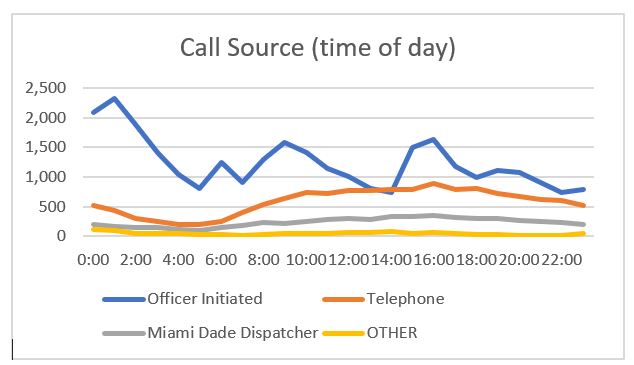

Specific attention should be paid to how to balance code 14 CFS, an officer-initiated effort to address community issues or a generated CFS for visible policing presence in identified hot spot locations in the jurisdiction, with the need to be responsive to CFS when they come in from the community. While code 14 accounts for the bulk of the CFS workload being reported by the agency in a given day, the NMPD should consider how to balance these proactive policing activities with the CFS during specific times of day to ensure there are enough officers in patrol to respond to telephone or dispatch CFS during peak times of the day such as the afternoon shift.

Figure 2. CFS by source, 2023

Source: NMPD-provided CFS data.

To better understand this issue, NMPD requested participation in the Northwestern Resource Allocation training. The training is a 3-day designed to provide an agency with the tools and skills needed to continually assess the level of staffing needed for the agency based on various roles of officers throughout a day. This data will be critical for NMPD to understand the full extent of their staffing needs for the agency, especially given the expected growth in North Miami in the next few years.

Recommendation 4.1b. The NMPD should consider how to partner with surrounding jurisdictions now and into the future for some specialized services to maximize available NMPD resources.

As the NMPD finds ways to maximize available funding and resources, there may be efficiencies in partnering with surrounding jurisdictions to provide similar levels of service to the community. This is especially true of units that have maintenance costs for equipment, training, and service animals.

Similar to the officer peer support partnership in development with a nearby agency, NMPD continues to examine how to leverage relationships with surrounding agencies to improve police services within North Miami and maintains a dialogue with agencies in the event there is a mutually beneficial opportunity.

Focus Area 5: Community Engagement

Finding 5.1: The NMPD maintains strong support from and connections to the North Miami community; however, there are opportunities to be strategic about community policing and problem-solving activities and efforts.

- Community outreach and community engagement is a priority for the NMPD. The agency values regular and meaningful interactions with the community. In addition, many specialized units’ regular activities include external-facing interactions with the community.

- For example, the K-9, marine, and mounted units all play different roles in public events as well as regular interactions with the community when deployed.

- The NMPD also has active community programming throughout the year including autism awareness, community bike rides, coffee with the chief, childhood cancer awareness, and other local and national engagement initiatives.

- In addition, the Police Athletic League coordinator actively engages at-risk students with supports including mentoring, academic, and emotional supports as well as serving as a liaison in schools.

- In addition, Chief Gause is actively engaging the community as she develops the agency’s strategic plan, which has not been updated in more than 10 years. The agency’s commitment to engaging the community in the plan is important.

The NMPD conducts a range of outreach efforts including social media, in-person events, and branding of police cars for particular interests and causes. For example, a review of the last three months of activities between February and April 2024 for the COPS unit shows that officers participated in various school career days, job fairs, and community outreach events such as festivals and activities. This is in addition to the regular postings from the agency on public safety notices and the NMPD’s upcoming engagement activities. - While the NMPD maintains thoughtful, consistent, and meaningful community outreach within North Miami, it has the opportunity to develop avenues for additional engagement and problem solving with the community. As NMPD continues to prioritize meaningful interactions with community, there are opportunities for NMPD to engage in collaborative problem solving with the community on persistent or emerging issues. For example, the NMPD could consider problem solving with the community on known issues of importance such as traffic congestion, theft and burglary, or code enforcement. All were common areas of concern that officers noted when speaking about issues they address on a regular basis in the community.

Recommendation 5.1a. The NMPD should consider how to codify community voices into regular and meaningful ways for strategic and operational planning within the agency.

The NMPD should consider how to regularly gather feedback from a representative group of community members and organizations on agency activities. This feedback could be in the form of a Chief’s Advisory Council or similar mechanism to ensure regular interactions throughout the year.

In addition, the NMPD should implement a public feedback channel publicizing actions taken because of input provided from the group. This is an important aspect of transparent community involvement in policing. Not all recommendations and feedback from the community will be actionable by the NMPD, but it is important to provide a way for the public to understand how and where community input is being incorporated into NMPD programs, policies, and operations.

The COPS Office recently released insights from fellow agencies on this topic in a publication titled Operationalizing Proactive Community Engagement: A Framework for Police Organizations. This guide is intended to present police leaders with a framework for institutionalizing community engagement strategies to improve their personnel’s willingness to increase proactive, positive interactions with the community.

NMPD is actively developing a strategic plan for the agency. Prior to participation in CRI, NMPD conducted a survey of the community to understand the perceptions of NMPD and NMPD services in the community. In addition, Chief Gause is prioritizing development of a strategic plan to support the direction of the agency over the next 3 years. In September 2024, CRI will be engaging in a strategic planning workshop that will support this recommendation for the agency.

Recommendation 5.1b. The NMPD should maintain and expand on community engagement efforts to include greater use of and training for collaborative problem solving.

“Community policing is a philosophy that promotes organizational strategies that support the systematic use of partnerships and problem-solving techniques to proactively address the immediate conditions that give rise to public safety issues such as crime, social disorder, and fear of crime.”

The NMPD should identify ways for COPS officers and officers more generally to collaborate with various communities throughout the jurisdiction on emerging or persistent issues facing those communities. These collaborative efforts develop stronger connections with the community and the officers that support those communities. The NMPD should consider how to align this outreach with the chief’s strategic plan and provide training opportunities for officers to increase their understanding and real-world use of problem solving with the community.

In addition, the NMPD should think strategically at the command staff and watch commander level to identify where and how it can leverage relationships in the community to achieve public safety goals. The NMPD should take efforts to specifically identify and prioritize problems that are of most concern to the community and to the department. NMPD command staff and watch commanders should then develop crime fighting and problem-solving strategies to address these issues, train officers on these approaches, deploy them in the field, and communicate these NMPD efforts back to the community to inform them about progress and gain additional feedback on those efforts.

The NMPD should find ways to integrate these steps of a comprehensive approach to community-based problem solving throughout the organization.

Additional information on the community policing model problem-solving model can be found in the COPS Office publication Community Policing Defined, and various problem-solving resources and models can be found both at the COPS Office website and at https://www.popcenter.org.

NMPD continues to consider how to integrate problem solving into their community engagement approach. Through the CRI program, NMPD is sending 4 officers to the Problem-Oriented Policing Conference in September 2024. This conference will provide NMPD the opportunity to hear from agencies from across the country on how they have been integrating problem-oriented policing approaches into their agencies and the impact these efforts can have on crime, community engagement, and officer engagement. This will help give NMPD new and different perspectives on this topic.

Finding 5.2. With a 2024 Florida statutory change in civic participation related to police oversight, the NMPD has the opportunity to reinvest in community policing and partnerships.

- A Florida law passed in April 2024 disbanded all community investigative boards. The North Miami Citizens Investigative Board closed on July 1, 2024. The CRI OA team interviewed members of the board during the initial site visit, and the members reported receiving few complaints about the conduct of NMPD officers; overall, they were satisfied with the level of service the NMPD provides to the community. While this form of formal civic participation is ending for North Miami, the NMPD should consider how to continue to engage in regular interactions and dialogue with the community on issues such as police accountability and transparency in police operations.

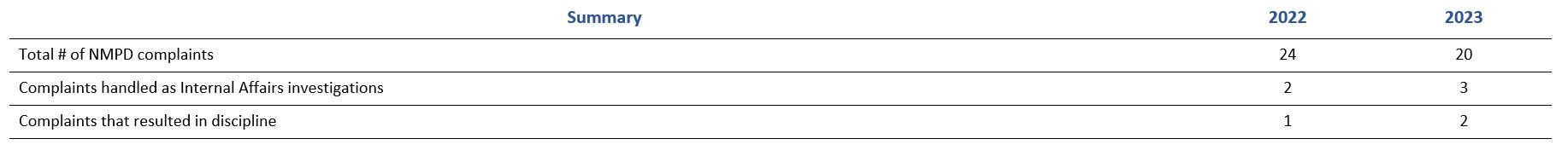

An examination of the NMPD’s internal affairs complaint data (table 3) confirmed that there were only 20 complaints in 2023, of which five of those complaints were not sustained or the officer was exonerated based on investigation by a supervisor, three proceeded to Internal Affairs (IA) investigations, and two of those IA investigations resulted in discipline. A similar trend occurred in 2022, with 24 complaints, including one complaint filed in the wrong jurisdiction and forwarded to the appropriate agency, two complaints resulting in Internal Affairs investigations and one of the IA investigations resulting in discipline. The remaining complaints were handled at the supervisor level for compliance with policy or changes in officer behavior. NMPD should also continue to assess its complaint processes to ensure that community members are able to submit complaints anonymously through a variety of ways including in-person, phone, and electronically and are not encountering barriers to filing complaints.

Table 3. NMPD internal affairs complaint data 2022–2023

Recommendation 5.2a. Identify ways to effectively and methodically capture, synthesize, and disseminate all of the NMPD’s community engagement efforts with the community and within the agency.

After initial site visits and reviews of initial data, it is clear that the agency values regular community engagement and interactions. As the NMPD continues to consider how to meaningfully integrate the community into NMPD activities and operations, it is equally important to document and disseminate these interactions within the community and the agency. Many of the NMPD’s social media team’s activities are helping capture and highlight these interactions. In addition, the NMPD annual report does an excellent job highlighting key community activities and agency priorities. The NMPD should also consider how to continue to raise awareness, such as with internal or external calendars available on the NMPD website and roll-call announcements of upcoming NMPD events in the area. These efforts can also help the NMPD identify and cultivate partnerships with community organizations with which NMPD interacts on a regular basis throughout the year.

As mentioned earlier, one of the key components of the COPS Office’s Operationalizing Proactive Community Engagement: A Framework for Police Organizations is to establish proactive community engagement and accountability including establishing measurable goals, outputs, and outcomes to gauge community engagement and involvement. Being able to regularly measure goals and the success of community engagement activities requires that the NMPD comprehensively understand and gather data on these activities as well.

NMPD plans to consider and incorporate this recommendation into their policing approach and support for the community but has yet to establish how they will address it.

Focus Area 6: Oversight and Accountability

No initial findings and recommendations.

Contact Information

Feedback and inquiries on the North Miami Police Department Organizational Assessment can be submitted via email to CRIOA+NorthMiami@cna.org. Please use the subject line “North Miami Police Department OA.”

Official websites use.gov

Official websites use.gov Secure .gov websites use HTTPS

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS