- Public Health Approaches for Law Enforcement

- Boston Public Health Commission

- New Report for Sex Trafficking Investigators

- Preventing Officer Suicide

- 2014 Sutin Award Nominations

- CHP Now Open

- CPD and CRI-TA Now Open

- MYVP Initiative Announced

- National Center for Building Community Trust

- Medal of Valor Nominations

Preventing Law Enforcement Officer Suicide

Suicide is a significant public health problem that touches people from all backgrounds. The statistics are staggering: In 2010, more than 38,000 people died by suicide;1 and in 2011, more than 1 million adults reported making a suicide attempt and more than 8 million adults seriously thought about attempting suicide.2 The impact of suicide is far-reaching emotionally and economically, affecting families, friends, coworkers, and many others.

Suicide is a significant public health problem that touches people from all backgrounds. The statistics are staggering: In 2010, more than 38,000 people died by suicide;1 and in 2011, more than 1 million adults reported making a suicide attempt and more than 8 million adults seriously thought about attempting suicide.2 The impact of suicide is far-reaching emotionally and economically, affecting families, friends, coworkers, and many others.

Each year, more law enforcement officers die by suicide than are killed in the line of duty.3 Officers are at a heightened risk for suicide, due to experiencing such risk factors as exposure to violence, suicide, or other job-related stressors; depression, anxiety, or other mental illness; substance abuse; domestic abuse; access to means to kill oneself (e.g., firearms); and poor physical health.4

However, there is a positive side to this story: Suicide is preventable—there is a growing will for suicide to be addressed; we have strategies and tools for suicide prevention—and if you are struggling with thoughts of suicide, there is help and hope. Below are ways you can help others or find help for you.

Everyone has a role in suicide prevention

The stakes of inaction are far too high when it comes to suicide. Consequences of suicidal behavior can include mental and emotional suffering, unproductive or absent staff, injury or disability, or even death, all of which can take a significant toll on law enforcement agencies, families, and communities.

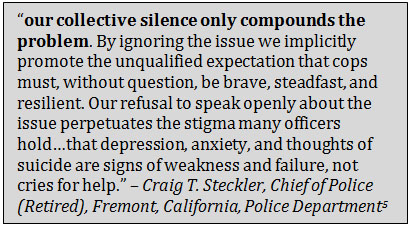

It is imperative that law enforcement agencies take action to prevent suicide and promote mental wellness. Care for officers' mental and emotional health should be on par with that for their safety and physical health. In order for prevention efforts to be successful, agencies must also address cultural and environmental barriers to prevention at all levels, e.g., the still-pervasive stigma that discourages at-risk officers from seeking help for fear of negative peer reactions or career ramifications; lack of comprehensive suicide prevention policies; and insufficient training for officers or health care providers.

It is imperative that law enforcement agencies take action to prevent suicide and promote mental wellness. Care for officers' mental and emotional health should be on par with that for their safety and physical health. In order for prevention efforts to be successful, agencies must also address cultural and environmental barriers to prevention at all levels, e.g., the still-pervasive stigma that discourages at-risk officers from seeking help for fear of negative peer reactions or career ramifications; lack of comprehensive suicide prevention policies; and insufficient training for officers or health care providers.

There are many people who have a role to play in preventing suicide among law enforcement officers. The attitudes and behaviors of chiefs, supervisors, peers, health care providers, family, friends, faith leaders, and others can all influence officers' health.

The National Strategy for Suicide Prevention6 (NSSP) outlines different roles people can play to prevent suicide. In law enforcement agencies, these roles can vary. For example: By prioritizing suicide prevention and enacting changes in agency-wide policies and practices, a chief can influence the culture change necessary for effective prevention efforts. By learning how to recognize and respond to warning signs for suicide, supervisors, peers, family members, and others can support at-risk officers and encourage them to seek the help they need. By effectively assessing and managing officers' suicide risk, health care providers can reduce risk and support resiliency and recovery. By engaging health care providers, peers, and families and enhancing policies and practices, agency leaders can more effectively respond after a suicide attempt or death.

One challenge for law enforcement agencies is a lack of access to informational resources to help address suicide. To help agencies adopt a comprehensive approach to suicide prevention and response, the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP), Bureau of Justice Assistance, U.S. Department of Justice, and EEI Communications compiled resources from agencies across the country that are available on IACP's Center for Officer Safety and Wellness website. Other resources are provided in “The Role of Law Enforcement Officers in Preventing Suicide,” a customized information page developed by the Suicide Prevention Resource Center.

Seeking and providing help

Another challenge comes from agencies being unprepared to support officers who are struggling, or officers being unaware of how to seek help for themselves. If you are struggling with thoughts of suicide, it's okay to seek help, which is a sign of strength, not weakness. Many people with similar struggles have been able to find hope, be resilient, and demonstrate that recovery is possible. Talk with a family member; a peer; your supervisor; your agency leadership; an EAP representative; a healthcare provider; the confidential National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (1-800-273-8255); or Safe Call Now (1-206-459-3020), which is a crisis line for public safety employees, to get the support and treatment you deserve.

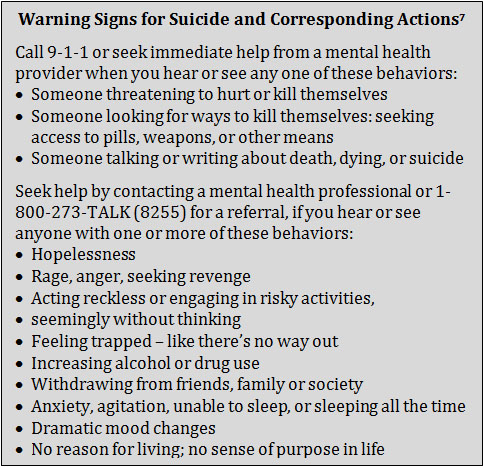

If you know someone at risk of suicide, there are steps you can take to assist them in getting help. If you know the warning signs of suicide, can suggest available referral and treatment options, and can provide social support, you will be better able to help an officer establish a stronger will to go on living and ultimately pull through. Below are trainings that can teach you how to recognize and respond to the signs of suicide risk:

If you know someone at risk of suicide, there are steps you can take to assist them in getting help. If you know the warning signs of suicide, can suggest available referral and treatment options, and can provide social support, you will be better able to help an officer establish a stronger will to go on living and ultimately pull through. Below are trainings that can teach you how to recognize and respond to the signs of suicide risk:

- In Harm's Way: Law Enforcement Suicide Prevention8 – This is a train-the-trainers program that prepares attendees to train administrators, officers, and staff on: recognizing and responding to suicide risk; reducing stigma around help-seeking behavior; and developing policies, protocols, and procedures to address at-risk officers.

- Question, Persuade, Refer (QPR) for Law Enforcement9 – This is an online certificate program that teaches law enforcement professionals how to recognize and respond to suicide risk. The program also includes advanced coursework that covers suicide risk assessment and management.

Moving forward

There are several recent and forthcoming advancements that can help you carry out this important work. The IACP, with support from the COPS Office, has just issued a report on law enforcement suicide and mental health that will serve as a national strategy for the prevention of suicide among law enforcement officers. Agencies can use this strategy to affect culture change and comprehensively address suicide prevention, intervention, and aftercare. The National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention (Action Alliance), the public-private partnership advancing the NSSP, has released a video on law enforcement officer suicide, featuring law enforcement professionals of all ranks who are committed to this important work. The Action Alliance has also launched a framework to help the public communicate more successfully about suicide and suicide prevention—by focusing messaging on social support, treatment, hope, resilience, and recovery—to help transform attitudes, beliefs, and cultural norms.

At the Action Alliance, our vision is a nation free from suicide. I encourage you to share in this vision, to make suicide prevention a high priority in your agency and your community, to support colleagues in need, and to ask for help when needed. Together, we can save lives.

Katherine Deal, MPH

Deputy Secretary

National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention

References

1 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center on Injury Prevention and Control. “Injury Prevention and Control: Data and Statistics.” http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/fatal.html.2 Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2012. Results from the 2011 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Mental Health Findings. Washington DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. http://www.samhsa.gov/data/NSDUH/2k11MH_FindingsandDetTables/2K11MHFR/NSDUHmhfr2011.htm#2.3.

3 International Association of Chiefs of Police. “Preventing law enforcement officer suicide.” http://www.theiacp.org/Preventing-law-Enforcement-officer-suicide.

4 Hackett, Dell P., and John M. Violanti. 2003. Police suicide: Tactics for prevention. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas Pub Ltd.

5 Steckler, Craig T. 2013. “IACP: Breaking the Silence on Law Enforcement Suicides,” President's Message, featured in The Police Chief. 80 (July): 6. http://www.policechiefmagazine.org/magazine/index.cfm?fuseaction=display_arch&article_id=2963&issue_id=72013.

6 Office of the Surgeon General and National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention. 2012. 2012 National Strategy for Suicide Prevention: Goals and Objectives for Action. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, September. http://actionallianceforsuicideprevention.org/NSSP.

7 Suicide Prevention Resource Center. “Best Practices Registry for Suicide Prevention: Warning signs for suicide prevention.” First posted May 4, 2007. http://www.sprc.org/bpr/section-II/warning-signs-suicide-prevention.

8 Suicide Prevention Resource Center. “Best Practices Registry for Suicide Prevention. In Harm's Way: Law Enforcement Suicide Prevention.” First posted April 9, 2012. http://www.sprc.org/bpr/section-III/harm%E2%80%99s-way-law-enforcement-suicide-prevention.

9 Suicide Prevention Resource Center. “Best Practices Registry for Suicide Prevention. Question, Persuade, Refer (QPR) for Law Enforcement.” First posted on May 14, 2012. http://www.sprc.org/bpr/section-III/question-persuade-refer-qpr-law-enforcement.

Public Health Approaches for Law Enforcement | Boston Public Health Commission | New Report for Sex Trafficking Investigators | Preventing Officer Suicide | 2014 Sutin Award Nominations | CHP Now Open | CPD and CRI-TA Now Open | MYVP Initiative Announced | National Center for Building Community Trust | Medal of Valor Nominations