A Different Response to Intimate Partner Violence

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) is a community crime problem that costs the United States more than $5.8 billion every year.1 IPV is a major drain on law enforcement resources involving a high volume of calls and repeated calls to the same location, consuming large amounts of time and often resulting in injuries or death. Intimate partner homicides make up 40–50 percent of all murders of women in the United States.2 Women who have experienced a history of IPV report more health problems than other women; they have a greater risk for substance abuse, unemployment, alcoholism, and suicide attempts (CDC). So how could a national problem, so costly and harmful to families and children, persist year after year? Are these offenders resisting “our best efforts”?

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) is a community crime problem that costs the United States more than $5.8 billion every year.1 IPV is a major drain on law enforcement resources involving a high volume of calls and repeated calls to the same location, consuming large amounts of time and often resulting in injuries or death. Intimate partner homicides make up 40–50 percent of all murders of women in the United States.2 Women who have experienced a history of IPV report more health problems than other women; they have a greater risk for substance abuse, unemployment, alcoholism, and suicide attempts (CDC). So how could a national problem, so costly and harmful to families and children, persist year after year? Are these offenders resisting “our best efforts”?

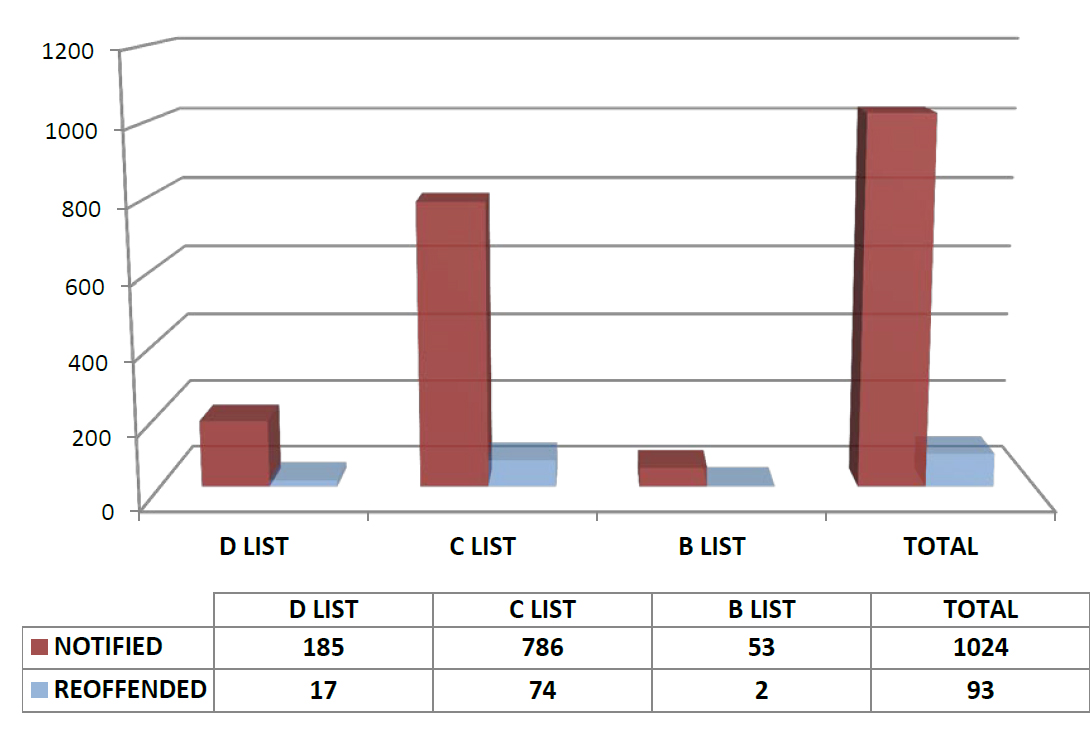

For the community of High Point, North Carolina, our answer was no, it was time for an innovative approach to this problem. Now, two years after full implementation of a completely different approach designed to hold the offender accountable, we offer hope that we have found what “our best efforts” look like. The strategy applies the evidence-based focused deterrence approach to the problem of IPV and shifts to an offender focus in combatting domestic related violence. One of the strategy’s critical features is the ability to focus on offenders at earlier stages of offending before the secrecy of offending entrenches and violence escalates. Research suggests that early intervention is key in stopping the cycle of IPV. The first two years of implementation resulted in re-offense rates of only nine percent across more than 1,000 offenders. These rates for IPV offenders are significant given the rates for IPV offenders in the literature, which range from 20 to 34 percent.

For the community of High Point, North Carolina, our answer was no, it was time for an innovative approach to this problem. Now, two years after full implementation of a completely different approach designed to hold the offender accountable, we offer hope that we have found what “our best efforts” look like. The strategy applies the evidence-based focused deterrence approach to the problem of IPV and shifts to an offender focus in combatting domestic related violence. One of the strategy’s critical features is the ability to focus on offenders at earlier stages of offending before the secrecy of offending entrenches and violence escalates. Research suggests that early intervention is key in stopping the cycle of IPV. The first two years of implementation resulted in re-offense rates of only nine percent across more than 1,000 offenders. These rates for IPV offenders are significant given the rates for IPV offenders in the literature, which range from 20 to 34 percent.

The idea for our approach came from Professor David M. Kennedy, the director of the Center for Crime Prevention and Control at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York. Prof. Kennedy believes the focused deterrence approach that has proven effective at controlling gang, gun, and drug-related violence can likewise be adapted to control IPV offenders. Kennedy suggests that not enough attention has been paid to controlling the offender. Traditional approaches have been victim-focused with heavy emphasis on helping victims avoid patterns of abuse, on disengaging from abusers, and on physically removing themselves from abusive settings. What if, in addition to providing services for the victim, we used very focused formal and informal sanctions against the offender? Can the IPV offender be held accountable with real predictable consequences without creating additional harm for the victims?

The idea for our approach came from Professor David M. Kennedy, the director of the Center for Crime Prevention and Control at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York. Prof. Kennedy believes the focused deterrence approach that has proven effective at controlling gang, gun, and drug-related violence can likewise be adapted to control IPV offenders. Kennedy suggests that not enough attention has been paid to controlling the offender. Traditional approaches have been victim-focused with heavy emphasis on helping victims avoid patterns of abuse, on disengaging from abusers, and on physically removing themselves from abusive settings. What if, in addition to providing services for the victim, we used very focused formal and informal sanctions against the offender? Can the IPV offender be held accountable with real predictable consequences without creating additional harm for the victims?

The High Point Police Department (HPPD) formed a partnership early in 2009 with researchers, practitioners, prosecutors, and members of the community to develop, implement, and evaluate a focused deterrence initiative targeted at the chronic IPV offender. The goals for the initiative are

- protect most vulnerable women from most dangerous abusers;

- take the burden of addressing abusers from women and move it to state/police;

- focus deterrence, community standards, outreach and support on most dangerous abusers;

- counter/avoid “experiential effect” (right or wrong lesson learned from experience of other offenders);

- take advantage of opportunities provided by offender’s variety of offenses;

- avoid putting women at additional risk.

Despite the widespread belief that IPV is qualitatively different from other types of violence, our research shows it is not. Our analysis of ten years of arrest data tells us the repeat IPV offender in High Point has a lengthy criminal history beyond intimate partner violence. In fact, offenders’ criminal histories were similar to those of the gang and drug offenders whom the focused deterrence approach had proven so effective at controlling. The IPV offenders studied averaged 10 arrests, assaults were the predominant charge but all included assaults other than for IPV, and 93 percent were unemployed. Because these offenders have rich criminal histories and are known to the criminal justice system they can be identified based on past behavior.

Despite the widespread belief that IPV is qualitatively different from other types of violence, our research shows it is not. Our analysis of ten years of arrest data tells us the repeat IPV offender in High Point has a lengthy criminal history beyond intimate partner violence. In fact, offenders’ criminal histories were similar to those of the gang and drug offenders whom the focused deterrence approach had proven so effective at controlling. The IPV offenders studied averaged 10 arrests, assaults were the predominant charge but all included assaults other than for IPV, and 93 percent were unemployed. Because these offenders have rich criminal histories and are known to the criminal justice system they can be identified based on past behavior.

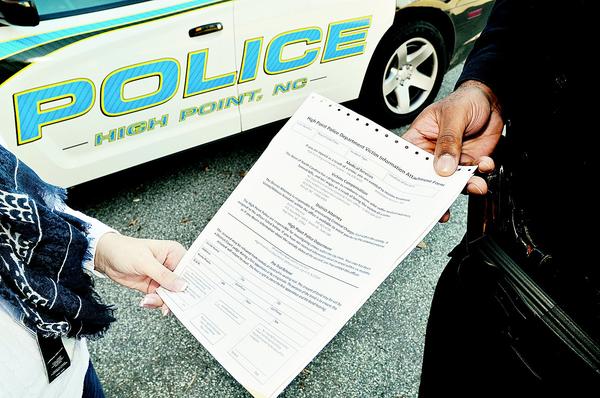

A new discovery came when research pointed out there are four very different levels of offenders, which led the team to develop a specific notification and sanction regime for each level. They range from the most violent, who have extensive criminal records, to those contacted on the first call, who have never been charged with an IPV offense. Table 1 shows the criteria established to properly match the offender to the response.

The measurable impact of this strategy so far includes a dramatic reduction in IPV-related homicides, lower recidivism rates for IPV offenders notified, reduction in IPV arrests, reduction in victim harm reported in IPV assaults, and fewer repeat calls for service. In the five years since the shift to this strategy (2009–2013), only one of the 16 homicides in High Point was IPV, as compared to 17 of 52 in the five years (2004–2008) before. In other words, prior to 2009, 33 percent of homicides were IPV, compared to six percent since. It should be noted that the “A” list offenders, the most violent, were initially identified in 2009 and targeted as examples before notification began to the “B”–“D” levels of offenders. For context, in 2013, Guilford County (the county containing almost all of High Point) experienced 26 homicides, of which 13—or 50 percent— were IPV. As stated earlier, the average recidivism rate for all levels of offenders is nine percent. A look at the breakdown between levels shows even the “B” list offenders can be deterred at a high rate. Comparing years 2012 and 2013, IPV arrests are down 17 percent, IPV arrests with reported victim injuries are down 19 percent, and IPV-related calls for service are down 10 percent.

A 2013 U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Community Oriented Policing Services award is funding a formal evaluation conducted by our research partner, the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, led by Stacy Sechrist, Ph.D. and John Weil; however, these initial findings are what give this strategy so much hope. If this strategy can be replicated in other cities with the same outcomes, this can be a signal moment for how we give intimate partner violence “our best efforts”.

Marty A. Sumner, Chief of Police

High Point (North Carolina) Police Department

References

1 Costs of Intimate Partner Violence Against Women in the United States (Atlanta, GA: National Centers for Injury Prevention and Control, 2003). www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/ipv_factsheet2012-a.pdf2 www.nij.gov/topics/crime/intimate-partner-violence/pages/extent.aspx

A Different Response to IPV | Using GPS Technology to Address Theft | Spreading a Cure for Crime | Child Sexual Abuse and Girls | New Film to Help LE and Communities | Reentry Round-Up Conference Registration Now Open