Shift Scheduling May be Key to Improving Health and Cutting Costs

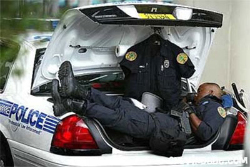

Community policing requires alert, well-rested officers who engage their communities in positive ways, and there may be things agencies can do to help reduce fatigue, improve officers’ quality of life at work, and more efficiently allocate resources. A recent experiment conducted in Arlington, Texas, and Detroit, Michigan, by researchers at the Police Foundation (Amendola, Weisburd, et al. 2011) demonstrated that officers who worked four 10-hour days followed by three days off averaged significantly more sleep than those working 8-hour shifts—actually gaining nearly 185 hours of sleep (the equivalent of 23[1] additional nights annually). In addition, these officers worked 80 percent less overtime on the job, potentially resulting in a cost savings to the department and a potential cost savings in terms of improved health possibly due to the increase in hours slept.

While many agencies have maintained the traditional five day, 40-hour week, a recent survey showed a trend away from this schedule. In 2005, 40 percent of agencies reported running 8-hour shifts, but by 2009, that number had dropped to 29 percent. Although many law enforcement agencies rely on 8-hour schedules, a 10-hour schedule can be a viable alternative to consider as it is likely to improve officers’ reported quality of work life, while increasing the hours officers sleep and reducing overtime costs. Nevertheless, agencies need to carefully consider how they might implement a 10-hour shift, taking into consideration the overall hours worked per year and maximizing the additional six hours per day introduced with each of three shifts working two extra hours.

Schedules that include four-on followed by four-off actually result in less overall hours worked in a year, and as a result, increase agency costs when considering overall hours worked. Remedies such as requiring officers to come in on days off for training, or other strategies, may address this concern. A fixed four-on, three-off schedule eliminates that concern, although it can create periods in which there are more officers than necessary. Therefore, agencies must take into consideration when their peak demand periods are, when they need increased staff, and how to sufficiently cover the fifth day, as officers are working one day less per week. When considering three shifts per day, the agency has an overlap during the six additional hours (24 hours versus 30 hours). These overlaps can be used to an agency’s advantage for increased field staffing at peak demand periods, or additional time for completion of reports or training, if it can be accommodated in an efficient manner.

When considering strategies to improve efficiency and cut costs, many agencies have considered reducing shifts to just two per day, requiring 12-hour shifts[2]. However, the purported cost savings may not be worth it if increased fatigue is the result. The Police Foundation study showed that those working 12-hour shifts reported lower levels of alertness at work and increased sleepiness, although these did not translate to worsened performance or other negative outcomes. Other studies have demonstrated negative health and safety consequences in other industries. The experimental study by the Police Foundation showed that other than a reduction in overtime, the benefits from the 10-hour shifts were not experienced by those on 12-hour shifts. Furthermore, as with the 10-hour shift, agencies need to consider how to schedule the 12-hour shift so as to comply with the contract, typically a 40-hour work week. In some agencies, officers work three 12-hour shifts in week one, followed by the same schedule in week two, but with a fourth 8-hour day tacked on every other week. This also can present complications in terms of staffing coverage at key times and how to best allocate personnel.

Another important consideration is the extent to which various individuals can cope with schedule changes, such as longer days and the potential health outcomes. Past research has indicated that age or certain health conditions may influence resiliency and coping with longer work hours. As a result, any scheduling strategy should include a consideration of policies on maximum hours worked per shift and per week inclusive of both overtime and off-duty employment.

Many agencies are experiencing cost reductions and budget shortages. Community policing presents cost efficient approaches to preventing and solving crime, as well as opportunities for increasing public confidence and reducing fear in communities. Law enforcement agencies can use scheduling practices as a means to improve efficiency and cost effectiveness, while at the same time improving the quality of life and health of their officers. Ultimately these improvements are likely to result in long run cost reductions as well (reduced sick leave, health-related problems, accidents and injuries, etc.), not to mention monetary savings from overtime paid. While reduced overtime saves money in the short run, it is likely to contribute to longer-term reductions in health care costs and increased safety.

The study of shift length provides important information for law enforcement leaders (management and union), as well as other policy makers, to consider when examining the most efficient and effective practices in their agencies. While many issues in policing seem to threaten management prerogatives or union protections, the issue of how scheduling occurs is one in which both have a solid vested interest, particularly as it relates to the health, safety, and welfare of officers, as well as the efficient use of resources. Perhaps the most important result of carefully thought through scheduling practices is the ultimate safety and security of community residents.

Karen L. Amendola, PhD

Police Foundation

&

David Weisburd, PhD

George Mason University

This project was funded in part by the National Institute of Justice

Grant # 2005-FS-BX-0057

1 8-hours per night

Back To Top

2 Smaller agencies have adopted these at higher rates than mid-sized or large departments (Amendola, Slipka, et al. 2011).

Back To Top

References

Amendola, Karen L., Slipka, Meghan G., Hamilton, Edwin E., Soelberg, Michael, and Koval, Kristen. 2011. Trends in Shift Length: Results of a Random National Survey of Police Agencies. Washington, D.C.: Police Foundation. www.policefoundation.org/content/trends-shift-length.

Amendola, Karen L., Weisburd, David., Hamilton, Edwin E., Jones, Greg, Slipka, Meghan, Heitmann, Anneke, Shane, Jon M., Ortiz, Christopher, and Tarkghen, Eliab. 2011. The Shift Length Experiment: What we Know About 8-, 10-, and 12-Hour Shifts in Policing. Washington, D.C.: Police Foundation. www.policefoundation.org/content/shift-length-experiment.

A Day in the Life of a School Resource Officer | Shift Scheduling may be Key to Improving Health and Cutting Costs | Seattle LEADs on Law Enforcement Diversion | DECSYS: Automating Collaboration | 2013 CPD Program Coming Soon! | Did you know…?