What We Can Do About Street Harassment

Street harassment, or sexual harassment in public by strangers, is the most prevalent form of gender based violence according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). It includes following, staring, vulgar comments, groping, and other forms of gender-based violent speech. While street harassment is a global issue, it is not often directly prohibited. The closest existing laws in the United States are the Harassment laws, which are on the books in most jurisdictions. Those laws vary by state and are usually summary offenses akin to being drunk in public. They necessarily involve reporting of the behavior and apprehension of the offender, and do not address the motivation behind the harassment—the same motivation behind gender-based violence: exerting power because one can do so largely without successful resistance.

Street harassment, or sexual harassment in public by strangers, is the most prevalent form of gender based violence according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). It includes following, staring, vulgar comments, groping, and other forms of gender-based violent speech. While street harassment is a global issue, it is not often directly prohibited. The closest existing laws in the United States are the Harassment laws, which are on the books in most jurisdictions. Those laws vary by state and are usually summary offenses akin to being drunk in public. They necessarily involve reporting of the behavior and apprehension of the offender, and do not address the motivation behind the harassment—the same motivation behind gender-based violence: exerting power because one can do so largely without successful resistance.

Similar to physical forms of gender-based violence, street harassment is largely unreported, in part because reporting the problem is usually met with dismissal or minimization. Reporting is also low because of the culture surrounding street harassment. Society as a whole still focuses on those who’ve experienced harassment as having brought it on themselves in some way, instead of focusing on what we can do to stop the behavior altogether. We have to hold each other accountable, and reimagine the culture surrounding gender-based violence as one that values our communities enough to recreate them into nurturing and safe environments.

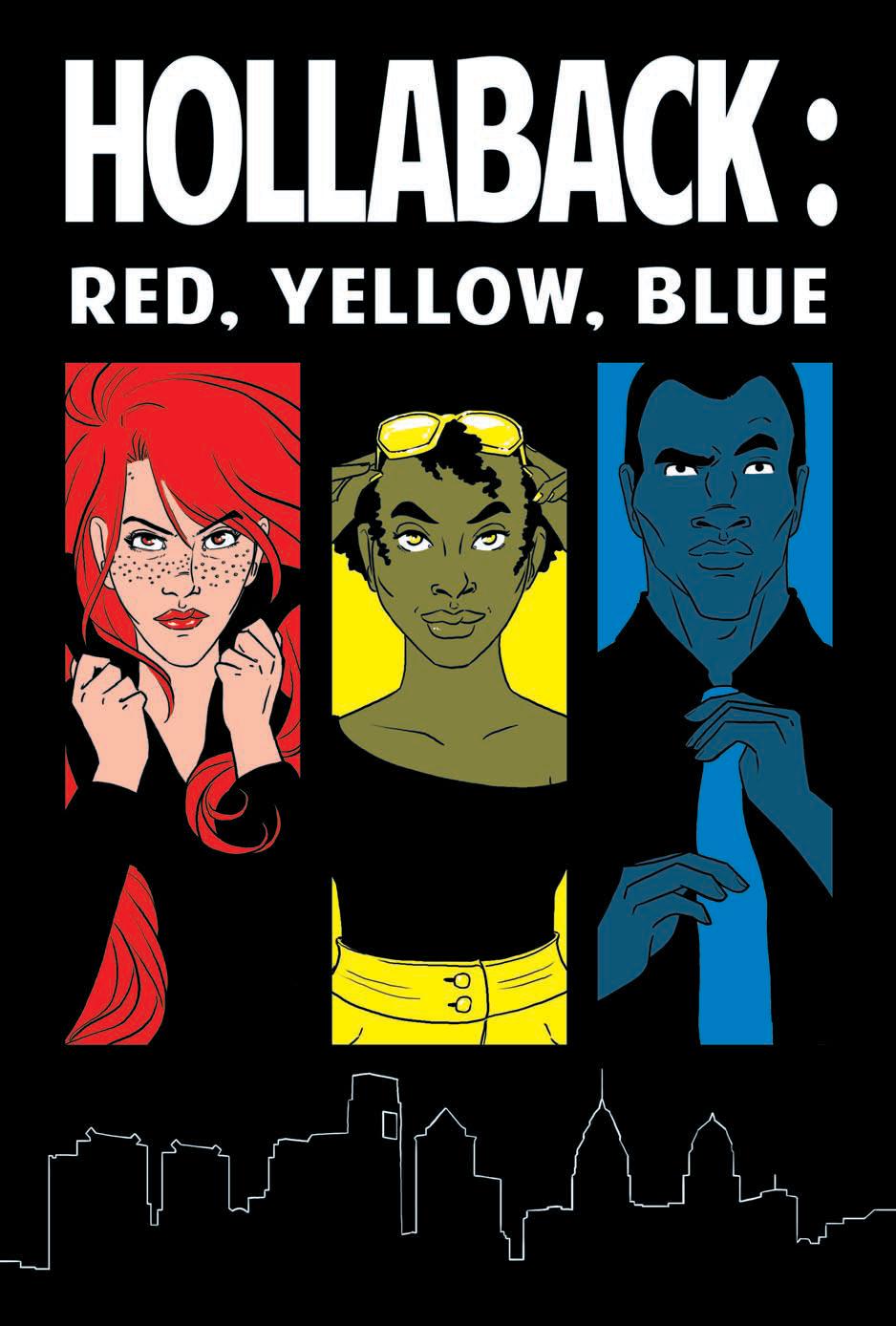

You might ask—if there’s nothing we’re trying to actively change on the criminal side of things, why should I care? The answer is that cultural change requires those responsible for policing public behaviors to be aware of and sensitive to actions that cause others to feel unsafe in their own communities. Hollaback! is an international, 62-branch network of local activists in cities all over the world working to end the permissive culture surrounding street harassment, one conversation at a time. Part of that activism involves collecting street harassment stories. Many branches have received stories outlining positive, supportive responses from law enforcement when they reported their street harassment. They have also collected stories of street harassment at the hands of law enforcement. When law enforcement engages in the very behavior that makes people feel unsafe in public, it reinforces that feeling of powerlessness, reminding people that even those who are here to protect don’t necessarily value and respect them enough to show them that respect. If we can’t lean on our law enforcement officers, how can we ever feel safe?

You might ask—if there’s nothing we’re trying to actively change on the criminal side of things, why should I care? The answer is that cultural change requires those responsible for policing public behaviors to be aware of and sensitive to actions that cause others to feel unsafe in their own communities. Hollaback! is an international, 62-branch network of local activists in cities all over the world working to end the permissive culture surrounding street harassment, one conversation at a time. Part of that activism involves collecting street harassment stories. Many branches have received stories outlining positive, supportive responses from law enforcement when they reported their street harassment. They have also collected stories of street harassment at the hands of law enforcement. When law enforcement engages in the very behavior that makes people feel unsafe in public, it reinforces that feeling of powerlessness, reminding people that even those who are here to protect don’t necessarily value and respect them enough to show them that respect. If we can’t lean on our law enforcement officers, how can we ever feel safe?

Law enforcement should also care about street harassment because it has a lasting effect on those who are harassed. Aside from restricting their mobility and safe-and-equal access to the cities in which they live, street harassment can cause lasting psychological and emotional damage. Akin to bullying in school, harassment based on appearance and gender identity causes many to question their own identities and self-worth. Additionally, being constantly evaluated by men in public for sexual appearance and desirability communicates to women that they are worth nothing more than their bodies. That evaluation system applies as much to those women who are harassed about their sexual desirability as it does to those who are not harassed and thus, in the silence of the harassers, told they are undesirable.

These two sides of street harassment can be described as “self-objectification”: people begin to internalize the objectifying harassment, or lack of harassment, and re-value themselves; reducing themselves to their bodies the way the harassers have reduced them. This leads to a new layer of self-doubt and insecurity that can impact peoples’ performance in school and work, and their overall happiness and self-esteem. That harmful form of self-evaluation is complicated even further when harassment attacks other portions of the person’s identity, whether it be race, sexual orientation, gender-representation, disabilities, or other externally visible characteristics of themselves.

These two sides of street harassment can be described as “self-objectification”: people begin to internalize the objectifying harassment, or lack of harassment, and re-value themselves; reducing themselves to their bodies the way the harassers have reduced them. This leads to a new layer of self-doubt and insecurity that can impact peoples’ performance in school and work, and their overall happiness and self-esteem. That harmful form of self-evaluation is complicated even further when harassment attacks other portions of the person’s identity, whether it be race, sexual orientation, gender-representation, disabilities, or other externally visible characteristics of themselves.

Since this issue is complex, and criminalization is not the ideal solution, law enforcement can assist in transforming this culture by keeping an open mind. Many Hollaback! branches receive stories about law enforcement being dismissive of reports that women were harassed, followed, and groped. “You don’t know the guy, we can’t find him. There’s nothing I can do for you,” are all common responses law enforcement is reported to have given to women attempting to report the behavior. That dismissal of a traumatic experience further enables street harassers, while telling those harassed that their experience and safety aren’t important. By joining us in this effort to understand and validate street harassment as a behavior that causes many women and LGBT people to feel unsafe in their own communities, law enforcement can create a culture that supports those who are harassed. Providing a sympathetic ear to people reporting harassment goes a long way in building trust in law enforcement, as well as sending the message that gender-based violence is intolerable. Additionally, directing harassed persons toward local and national Hollaback! sites can empower them by providing them with a sense of community on a global scale.

Rochelle Keyhan

Director of HollabackPHILLY

Executive Member, Board of Directors of Hollaback!

American Policing in 2022 Goes to Yale | SROs and Information Sharing | Preparing officers for a community oriented department | What we can do about street harassment | 2013 Sutin Civic Imagination Award | Medal of Valor and Badge of Bravery