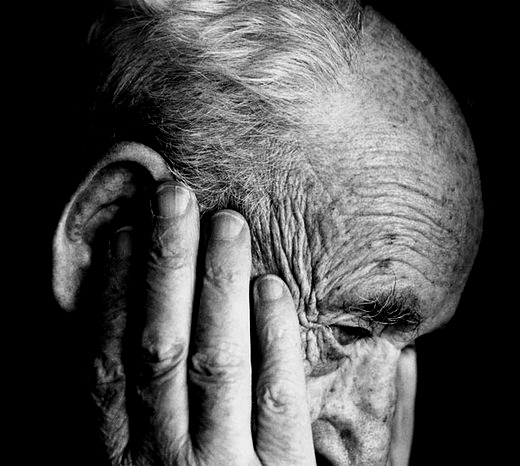

A Booming Problem: Alzheimer’s, Dementia, and Elder Abuse

They’re your neighbor, friend, grandparent, aunt, perhaps even your sibling or spouse—good people now living in the grip of a horrible illness: Alzheimer’s disease. According to the Alzheimer’s Association’s latest figures, over five million Americans suffer from this illness now, and every 67 seconds, somebody new is diagnosed with it. 1

Protecting these citizens, as well as those who suffer from other forms of dementia and the elderly whose physical disabilities make them vulnerable, is a growing challenge for law enforcement. In 2012, the number of Americans aged 65 and older was approximately 43 million; by 2040, when the last of the Baby Boomer generation will be in their 70s, that number will grow to almost 80 million. And though they don’t do so intentionally, many of these senior citizens will get into trouble or cause serious problems because of decreased mental or physical abilities.

500,000 new cases of Alzheimer’s each year

While most seniors have full command of their mental faculties, the number who suffer from dementia is growing steadily. The Alzheimer’s Association projects that about 16 million Americans will have this disease by 2050. In addition, there are about 60 other forms of dementia—as well as illnesses such as diabetes, which can also affect judgment and behavior.

As time goes on, police officers will more frequently become involved with these individuals or their caretakers—searching for lost family members, stopping drivers who should no longer be on the road, rescuing nursing home patients from abusive staff, or intervening in other crisis situations.

What will complicate these responses is the victims’ inability to understand, let alone explain, what they are doing or what is happening to them. They may also be afraid of their tormentors or wary of the world at large, including police officers. To make matters worse, some medical conditions can cause them to become uncooperative, disruptive, or even violent.

What will complicate these responses is the victims’ inability to understand, let alone explain, what they are doing or what is happening to them. They may also be afraid of their tormentors or wary of the world at large, including police officers. To make matters worse, some medical conditions can cause them to become uncooperative, disruptive, or even violent.

The real culprits: Medical conditions

A recent example is that of a 78-year-old diabetic man who was Tasered by police in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. When the man, who was driving erratically, crashed into parked cars, a responding officer tried to stop him. But he kept driving and hit another vehicle, then hit the police cruiser. Because the driver didn't obey commands to stop and reached for something on the seat when the officer approached, the officer thought the driver might be reaching for a weapon and used the stun device on him twice.

After responding firefighters determined that the driver was a diabetic with low blood sugar and treated him, the fire chief commented that diabetic individuals in that condition can become combative or angry. The Portsmouth deputy police chief, Corey MacDonald, added, "Our police officers are not paramedics. This driver could just as easily have been under the influence of alcohol or drugs or engaging in willful criminal conduct." 2

Searching for wanderers

But the most common cause of disruptive behavior and calls for help is dementia, Alzheimer’s in particular. Because of impaired memory and judgment, these individuals may forget to pay for things when shopping; call police about incidents that did not actually take place; or exhibit inappropriate, even criminal, behavior. They are also prone to wandering and if not found within 24 hours are likely to die or be seriously injured.

Police intervention is required in all of these incidents and is critical to finding a lost person. In response to increasing numbers of calls for this service, the Alzheimer’s Association developed the MedicAlert® + Alzheimer’s Association Safe Return® program, a free service that can help police access information for a search.

Most states also have systems for alerting the general public about missing persons, and there are GPS and other tracking systems available as well. And once a missing person is found, a caring, thoughtful approach can not only calm the lost individual but make the intervention go more smoothly.

A heart can remember

Law enforcement is frequently called to find a wandering senior and often responds compassionately as well as professionally. People all over the country were touched by the actions of the officers who found Melvyn Amrine wandering two miles from his Little Rock home in May of 2014. Through careful questioning, the officers had determined that though Melvyn could remember little else, he knew that it was Mother’s Day, and was in search of flowers to give his wife. In TV reports and a widely viewed YouTube video, the Little Rock officers could be seen not only finding Melvyn, but helping him buy flowers, even paying for them, then returning him to his grateful, tearful wife.

Because assisting people with dementia can be difficult, the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP) has developed a program to help first responders. Called the Alzheimer’s Initiative, it offers variety of materials as well as a website which provide tips for effective interactions. They offer the following suggestions to police officers who encounter a person with dementia:

Introduce yourself and say you are there to help. Smile, and speak slowly in a friendly voice. Ask simple questions and check for a tracking device or MedicAlert ID. If the person becomes agitated, change the topic to something pleasant, and provide security and comfort (e.g., blanket, water, or someplace to sit).

Do not take comments personally, argue with, or correct the person. Take care not to surprise them by approaching from behind without warning, and don’t touch them without asking or explaining. Also refrain from repeating a question too many times, which may provoke agitation.

Physical abuse and financial exploitation

In some cases, individuals with Alzheimer’s or other forms of dementia may become violent or abusive. But more often, they are the victims of physical and emotional abuse. A national study found that about 565,000 elderly people—not all of whom were suffering from dementia—reported experiencing abuse or neglect in 2003 alone.

Seniors are also frequent targets of con artists, who prey upon their confusion, trust, and reluctance to report problems to the police. These crimes are estimated to cost the elderly almost $3 billion a year in the United States; according to a study done by the MetLife Mature Market Institute and the National Committee for the Prevention of Elder Abuse, that figure is on the rise. 3

Rhode Island Attorney General Peter Kilmartin’s office opened 128 financial-elder-abuse cases in 2011, a 40 percent increase from 2010. And according to a 2012 report by the National Association of States United for Aging and Disabilities, almost 70 percent of state adult protective services agencies reported case load increases of up to 20 percent in the past five years. Paul Greenwood, a deputy district attorney in San Diego and head of the area’s elder-abuse protection unit, says his office will prosecute about 200 cases in 2013. “I’ve never been busier,” he said. 4

To make matters worse, the perpetrators are often family members or trusted friends and the victims too ashamed, afraid, or dependent on the person who bilked them to report the crime. “If she goes to prison, then who will take care of me?” is a common lament.

Innovative and Collaborative Solutions

The problems of this rapidly growing population—ranging from abuse to financial scams, disruptive behavior to missing persons—are varied and complicated, calling for a wide array of skills and related knowledge. Meeting these challenges also requires new approaches and a much higher degree of collaboration than has been the norm for local law enforcement.

Among the responses have been the Milwaukee Police Department’s Gray Squad, a senior citizen assault prevention unit that has primary responsibility for older victims and the Rhode Island Senior Citizens Police Advocate Program, which places an advocate for older people in every police department in the state. Some jurisdictions in California have also established dedicated courts to handle the growing number of elder-abuse cases.

Among the responses have been the Milwaukee Police Department’s Gray Squad, a senior citizen assault prevention unit that has primary responsibility for older victims and the Rhode Island Senior Citizens Police Advocate Program, which places an advocate for older people in every police department in the state. Some jurisdictions in California have also established dedicated courts to handle the growing number of elder-abuse cases.

Among other innovative approaches has been the Norfolk (Virginia) Sheriff’s Department’s Check and Respond Everyday (CARE) program, which uses a computer program to call and check in on adults several times a day. A similar program is the Glendale (California) Police Department’s volunteer-based “Caring Caller Program.” Community outreach efforts are effective too, especially those that educate the public about Alzheimer’s, dementia and elder care-related issues.

Law enforcement agencies can also improve their overall effectiveness in protecting the elderly and those with dementia through collaboration with social services, faith communities, and private and public organizations. Communications with adult protective service workers, emergency medical personnel, prosecutors, and others can help identify and respond to crime. Moreover, by sharing responsibilities and working together, agencies, state and national organizations can pool resources, reduce duplicative efforts, and save both time and money while providing better service.

Internally, agencies can prepare for the oncoming tide of Alzheimer’s and elder care-related problems by providing training and other resources to the entire staff from the top down. Though funding for some programs is flat, there are many resources that can help.

But timing in all of these efforts is important—the protection of the sick and elderly is an issue that must be reckoned with now. Baby Boomers have already started to cross the line into old age, and Alzheimer’s will affect us all in one way or another. It’s time to prepare for the fast growing challenges.

Faye Elkins

Special Contributor

The COPS Office

Resources

There are a number of organizations offering training and other support for responding effectively to the needs of the elderly and individuals with Alzheimer’s or other ailments. Below is a partial list.

The COPS Office’s Physical and Emotional Abuse of the Elderly Problem Specific Guide

USDOJ: Elder Justice Initiative

The International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP) Alzheimer’s Initiative Program

The Alzheimer’s Association Safe Return Guide for Law Enforcement

The Alzheimer’s Association First Responders Training Program

The FBI, Fraud Target: Senior Citizens

References

1 Alzheimer’s Association, “2015 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures,” alz.org, accessed April 13, 2015, http://www.alz.org/facts/overview.asp.2 Elizabeth Dinan, “Police Tase Diabetic Driver Who Hit Cars,” Seacoastonline.com, last updated February 3, 2015, http://www.seacoastonline.com/article/20150203/News/150209767.

3The MetLife Study of Elder Financial Abuse: Crimes of Occasion, Desperation, and Predation Against America’s Elders (National Committee for the Prevention of Elder Abuse, 2011), https://www.metlife.com/assets/cao/mmi/publications/studies/2011/mmi-elder-financial-abuse.pdf.

4 “Protecting Mom & Dad’s Money: What to Do When You Suspect Financial Abuse,” Consumer Reports, January 2013, http://www.consumerreports.org/cro/magazine/2013/01/protecting-mom-dad-s-money/index.htm.

May Photo Contest Winner | SROs and Students | Alzheimer's, Dementia, & Elder Abuse | Enhancing CP through GPS | 2015 COPS Solicitations | Sutin Award Nominations