National Network for Safe Communities: An Overview

On March 12, 2015, the National Network for Safe Communities, through a cooperative agreement with the U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS Office), will release Drug Market Intervention: An Implementation Guide, a practical tool for cities implementing this proven strategy to eliminate overt drug markets and the damage they cause to communities.

The National Network for Safe Communities, a project of John Jay College of Criminal Justice, was launched in 2009 by David M. Kennedy. The National Network supports cities implementing strategic interventions to reduce violence, minimize arrest and incarceration, enhance police legitimacy, and strengthen relationships between law enforcement and communities. With support from the COPS Office, the National Network provides strategic advising and research capacity in communities nationally, connects cities for peer learning, and advances innovations that support its strategies.

The National Network’s intervention model identifies a particular serious crime problem; assembles a partnership of law enforcement, community leaders, and social service providers; conducts research to identify the small number of people driving the majority of serious offending; responds to continued offending with a variety of sanctions; focuses services and community resources on offenders; and communicates with offenders directly and repeatedly to give them a moral message from the community against offending, prior notice of the legal consequences for further offending, and an offer of help.1 This model has a long history of reducing street group-involved violence and eliminating overt drug markets in communities nationwide,2 and some pilot sites have begun adapting it to problems such as domestic violence, prison violence, robbery, and community supervision.

The Group Violence Intervention (GVI) reduces group-involved homicide and shooting when community members and law enforcement join together to engage with group members at face-to-face “call-in” meetings and communicate a moral message against violence, a credible law enforcement message about the consequences of further violence, and a genuine offer of help. Pioneered by Kennedy and colleagues, it has proven effective in a variety of settings in a Campbell Collaboration evaluation3 and is currently being implemented in Chicago; New Orleans; Baltimore; Oakland, California; and many other cities. Group Violence Intervention: An Implementation Guide, published by the COPS Office, provides a practical guide for cities implementing GVI.4

Several practical innovations support cities implementing GVI. “Shooting scorecards” use police data and performance measurements to identify and rank the groups that commit the highest number of shootings and experience the highest number of shooting victimizations during a given time period. This ensures that law enforcement and the larger GVI partnership focus intervention resources on the groups that generate the most gun violence. Managing the Group Violence Intervention: Using Shooting Scorecards to track Group Violence, published by the COPS Office, provides a practical guide for cities using shooting scorecards within GVI.5

“Custom notifications” are a method for individualized, direct communication from the GVI partnership to particular group members. Used during home and street visits or in forum settings, custom notifications offer advantages to the strategy that call-ins cannot. They allow practitioners to communicate with high-risk “impact players;” to communicate quickly and tactically; and to incorporate individualized legal information into the message. They are a powerful tool to interrupt “beefs” between groups, avoid retaliation after incidents, calm outbreaks of violence, and reinforce the GVI message. They can include “influentials,” people who have a positive influence in group members’ lives. Custom Notifications: Individualized Communication in the Group Violence Intervention, published by the COPS Office, provides a practical guide for cities using custom notifications within GVI.6

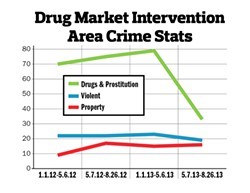

The Drug Market Intervention (DMI) effectively eliminates overt drug markets and improves life for residents of the surrounding communities. Overt drug markets operate in public, causing chaos, violence, and enormous damage to communities. DMI, which was first piloted in 2004 in High Point, North Carolina, identifies particular drug markets; identifies street-level dealers; arrests violent offenders; develops and suspends cases for nonviolent dealers to create certainty of consequences for further dealing; and brings together dealers, their families, law enforcement, social service providers, and community leaders for a call-in meeting that makes clear that selling drugs openly must stop. The strategy also includes an important, nationally-recognized process of “racial reconciliation” to address historic conflict between law enforcement and communities of color. Dozens of cities have implemented DMI with reductions in violent and drug-related crime, minimized use of law enforcement, strong endorsement from the community, and improved relationships between law enforcement and the community.7

The Drug Market Intervention (DMI) effectively eliminates overt drug markets and improves life for residents of the surrounding communities. Overt drug markets operate in public, causing chaos, violence, and enormous damage to communities. DMI, which was first piloted in 2004 in High Point, North Carolina, identifies particular drug markets; identifies street-level dealers; arrests violent offenders; develops and suspends cases for nonviolent dealers to create certainty of consequences for further dealing; and brings together dealers, their families, law enforcement, social service providers, and community leaders for a call-in meeting that makes clear that selling drugs openly must stop. The strategy also includes an important, nationally-recognized process of “racial reconciliation” to address historic conflict between law enforcement and communities of color. Dozens of cities have implemented DMI with reductions in violent and drug-related crime, minimized use of law enforcement, strong endorsement from the community, and improved relationships between law enforcement and the community.7

Many communities are using the National Network’s core approach and adapting it to address other serious crime problems. Most notably, High Point’s pilot Offender Focused Domestic Violence Initiative is showing promising early results in using this framework to identify and communicate with the most serious domestic violence offenders. Since implementation began, the city has seen dramatic reductions in reoffending among domestic abusers, as well as domestic violence arrests, calls for service, and victim injuries.8 With support from the COPS Office, the intervention will be replicated and evaluated in Lexington, North Carolina.

The National Network’s approach represents a workable way forward to reduce violence and incarceration; help police do their job in a way that does not harm, and in fact strengthens, the communities they serve; improve law enforcement-community relationships; and support communities in reclaiming their voice about the way they want to live.

Michael A. Friedrich

Senior Communications Associate

National Network for Safe Communities

References

1 D.M. Kennedy, “Pulling Levers: Chronic Offenders, High-Crime Settings, and a Theory of Prevention,” Valparaiso University Law Review 31, no. 2 (1997): 449–484, http://scholar.valpo.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1860&context=vulr; D.M. Kennedy, Deterrence and Crime Prevention: Reconsidering the Prospect of Sanction (London: Routledge Press, 2008).2 A.A. Braga, and D.L. Weisburd, “The Effects of ’Pulling Levers‘ Focused Deterrence Strategies on Crime,” Campbell Systematic Reviews 8, no. 6 (2012).

3 Ibid.

4 National Network for Safe Communities, Group Violence Intervention: An Implementation Guide (Washington, DC: Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, 2013), http://ric-zai-inc.com/Publications/cops-p280-pub.pdf.

5 Anthony A. Braga, David M. Hureau, and Leigh S. Grossman, Managing the Group Violence Intervention: Using Shooting Scorecards to Track Group Violence (Washington, DC: Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, 2014), http://ric-zai-inc.com/Publications/cops-p305-pub.pdf.

6 David M. Kennedy and Michael A. Friedrich, Custom Notifications: Individualized Communication in the Group Violence Intervention (Washington, DC: Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, 2014), http://ric-zai-inc.com/Publications/cops-p304-pub.pdf.

7 N. Corsaro and E.F. McGarrell, An Evaluation of the Nashville Drug Market Initiative (DMI) Pulling Levers Strategy (East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University, 2009), http://www.nnscommunities.org/NashvilleEvaluation.pdf; J.M. Frabutt, M.K. Hefner, K.L. Di Luca, and T.L. Shelton, “A Street-Drug Elimination Initiative: The Law Enforcement Perspective,” Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies and Management 33, no. 3 (2010), 454–472; J.M. Frabutt, T.L. Shelton, K.L. Di Luca, L.K. Harvey, and M.K. Hefner, A Collaborative Approach to Eliminating Street Drug Markets through Focused Deterrence, final report to the U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs, National Institute of Justice, June 2009, http://libres.uncg.edu/ir/uncg/f/T_Shelton_CollaborativeApproach_2009.pdf; M.K. Hefner, J.M. Frabutt, L.K. Harvey, K.L. Di Luca, and T.L. Shelton, “Resident Perceptions of an Overt Drug Elimination Strategy,” Journal of Applied Social Science 7, no. 1 (March 2013), 61–78, http://jax.sagepub.com/content/7/1/61.full.pdf; J.M. Frabutt, M.K. Hefner, L.K. Harvey, K.L. Di Luca, and T.L. Shelton, “Key Community Stakeholders in a Police-Community Partnership to Eliminate Street-Drug Markets: Roles, Engagement, and Assessment of the Strategy,” Crime, Punishment, and the Law: An International Journal 2, no. 1–2 (2009), 55–70.

8 S.M. Sechrist and J.D. Weil, “The High Point OFDVI: Preliminary Evaluation Results,” in D. M. Kennedy (chair), Using Focused Deterrence to Combat Domestic Violence, symposium presented at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice International Conference: The Rule of Law in an Era of Change: Security, Social Justice, and Inclusive Governance, Athens, Greece, June 2014, http://ncnsc.uncg.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/2014-June-John-Jay-Conference-Evaluation-Presentation.pdf; S.M. Sechrist, J.D. Weil, and M. Sumner, Offender Focused Domestic Violence Initiative in High Point, NC: Application of the Focused Deterrence Strategy to Combat Domestic Violence, presentation at the Biennial Conference of the North Carolina Coalition Against Domestic Violence, Greensboro, NC, May 2014, http://ncnsc.uncg.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/NCCADV-2014-Conference-Presentation.pdf.

March Photo Contest Winner | Stopping Violence | National Network for Safe Communities | Recap of Winter Conferences | 2015 Sutin Award Open