Contact Us

To provide feedback on the Community Policing Dispatch, e-mail the editorial board at CPDispatch@usdoj.gov.

To obtain details on COPS Office programs, publications, and resources, contact the COPS Office Response Center at 800-421-6770 or AskCopsRC@usdoj.gov

U.S. Department of Justice

Office of Community Oriented Policing Services

Washington, DC 20530

The era of community policing in the United States grew out of the period of civilian resistance and unrest of the 1960s and 1970s. Recognizing that police cannot solve public safety problems alone, community policing is a “philosophy that promotes organizational strategies that support the systematic use of partnerships and problem-solving techniques to proactively address the immediate conditions that give rise to public safety issues such as crime, social disorder, and fear of crime” (COPS Office 2014). The origins of community policing as practice can be traced to research on Team Policing in the 1970s conducted at the National Police Foundation and National Sheriffs’ Association in partnership with the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration (LEAA).

While community policing and its core components have been widely adopted across the criminal justice system, there has not yet been widespread guidance or information available about the potential benefits of implementing it in jails, despite the fact that former Fresno (California) Sergeant David Kurtze noted that “Far too often, local jails are left out of the picture, when they should be identified as the missing piece of the community-policing paradigm” (Kurtze 2000, 16). At the 2000 National Institute of Corrections (NIC) Large Jails Network Conference, attendees came to the realization that “The principles of community policing can be implemented in correctional facilities” and that “there is a need to look at incorporating its philosophy into facility operations” (NIC 2000, 33). In his conference presentation, Kurtze (2000) noted:

The jail population mirrors that in the community, so if community-oriented policing works on the outside, it should work inside the facility as well. It can improve inmate disciplinary problems and population management . . . and counter negative visions of corrections. Cooperating on projects can also improve the relations of law enforcement and corrections. Benefits to the officer include self-satisfaction achieved through solving problems . . . and a chance to make a real difference. (p. 31)

Perhaps not surprisingly, Kurtze’s assertion has not been widely tested, but evidence from a recent study conducted in the Los Angeles County (California) Sheriff’s Department appears to confirm it. After a community policing program—the “town sheriff” model—was tested in one classification/floor of the Los Angeles Men’s Jail, inmate grievances and disciplinary actions were reduced (Amendola, Valdovinos, and Thorkildsen 2019).

Subsequently, researchers from the National Police Foundation and their partners at the National Sheriffs’ Association were awarded a cooperative agreement from the COPS Office to develop a toolkit focused on implementing community policing and procedural justice in jails, recognizing that jails are reflections of the community—in fact, jails are communities. The toolkit is designed to provide sheriffs’ offices, jail administrators, and the wider corrections field with information about how agencies have implemented community policing and procedural justice practices in corrections and showcase programs and practices implemented by sheriffs and other jail personnel that reflect a community policing orientation.

In the upcoming months, the COPS Office will be releasing this toolkit, which will include

- an executive summary;

- results of a national survey of members of the National Sheriffs’ Association;

- featured programs that are case studies of jails in which specific programming captures the essence of community policing or components of procedural justice;

- a summary of the scientific literature on community policing and procedural justice;

- a strategy brief focused on addressing COVID-19 in jails;

- a promising practices guide featuring short synopses of community policing–type efforts geared at various aspects of jail management.

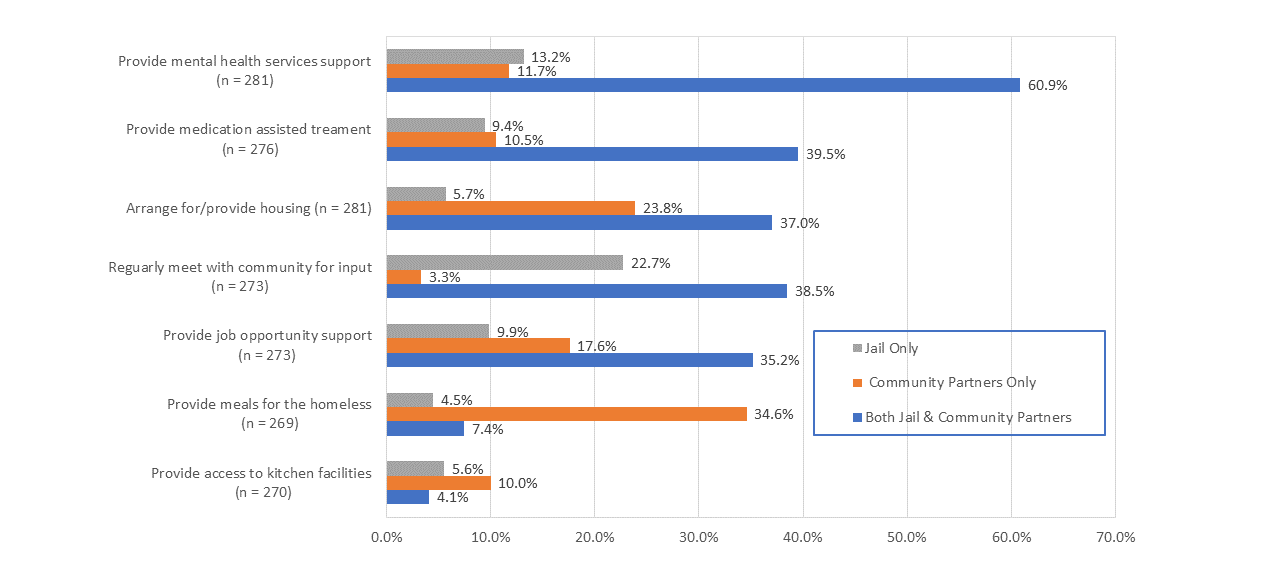

As shown in figure 1, an example of a key finding from the national survey is that more than 60 percent of participating agencies reported that they provide mental health services support as a form of community-based programming geared toward improving the quality of life for inmates. Similarly, almost 40 percent of those participating in the survey provide medication assisted treatment (MAT) for substance use with almost an equal proportion reporting that they have regular meetings with community members to seek input for problem solving, re-entry, or other collaborative activities that improve health and outcomes for the justice involved individual.

Figure 1. What do jails and their community partners do that involves community-based programming to improve quality of life?

It is anticipated that the toolkit will be widely shared with sheriffs, jail administrators, and community partners and will serve as a resource for modeling programs and practices that promote community policing and procedural justice in jails. Given that the average stay in jail is currently about 26 days (Zeng and Minton 2021), jail administrators and staff have a limited opportunity to provide substance use and mental health services, connect individuals with the types of services needed to enhance the opportunity for a successful re-entry, and address the underlying circumstances and conditions that give rise to crime. As a result, many agencies have adopted innovative programming to help individuals address the root causes of their incarceration in even the shortest of jail stays. The purpose of this toolkit is to showcase the types of community policing and procedural justice programs and strategies jail commanders and personnel could replicate to improve the overall community environment within their facilities, promote and enhance successful transitions back to residential communities, and create an improved safety and wellness climate in which all who live and work within the correctional facility can thrive.

Karen L. Amendola, PhD

Chief Behavioral Scientist

National Police Foundation

Maria Valdovinos-Olson, MA

Senior Research Associate

National Police Foundation

Ben Gorban, MS

Senior Project Associate

National Police Foundation

Carrie Hill, Esq.

Chief Jail Advisor

National Sheriffs’ Association

References

Amendola, Karen L., Maria Valdovinos Olson, and Zoë Thorkildsen. 2019. Promoting Health, Safety, and Wellness in Los Angeles County Jails. Volume I: An Outcome Evaluation of a Community Oriented Policing Model—The Town Sheriff Approach. Washington, DC: National Police Foundation.

COPS Office (Office of Community Oriented Policing Services). 2014. Community Policing Defined. Washington, DC: Office of Community Oriented Policing Services.

https://cops.usdoj.gov/RIC/Publications/cops-p157-pub.pdf.

Kurtze, David. 2000. Local Jails: The Missing Piece of the Community Policing Paradigm. Longmont, CO: National Institute of Corrections.

https://ntrl.ntis.gov/NTRL/dashboard/searchResults/titleDetail/PB2000105808.xhtml.

NIC (National Institute of Corrections). 2000. Proceedings of the Large Jail Network Meeting. Longmont, CO: National Institute of Corrections.

https://s3.amazonaws.com/static.nicic.gov/Library/016066.pdf.

Zeng, Zhen, and Todd D. Minton. 2021. Jail Inmates in 2019. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics.

https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/ji19.pdf.

Subscribe to Email Updates

To sign up for monthly updates or to access your subscriber preferences, please enter your email address in the Subscribe box.