Contact Us

To provide feedback on the Community Policing Dispatch, e-mail the editorial board at CPDispatch@usdoj.gov.

To obtain details on COPS Office programs, publications, and resources, contact the COPS Office Response Center at 800-421-6770 or AskCopsRC@usdoj.gov

U.S. Department of Justice

Office of Community Oriented Policing Services

Washington, DC 20530

According to a U.S. Department of Health and Human Services publication on child maltreatment, in fiscal year 2020, approximately 618,000 children in the United States experienced abuse and neglect, and 1,750 died as a result. Though these cases tug at their heartstrings, responding law enforcement professionals are often not trained to handle the special needs of traumatized children. Investigating such crimes requires a delicate balance between sensitivity and fact-finding, interview techniques that put the child at ease while establishing a case that can be successfully prosecuted. Children are often intimidated by law enforcement, fearful of retribution by the offender, and easily led to tell an adult what they think the adult wants to hear.

But forensic interviewers specially trained in age-appropriate techniques for questioning children can gather facts and findings that can stand up to scrutiny in court without further distressing the young victims. These specialists often work in multidisciplinary teams (MDT) that include professionals from victim advocacy, child protective services, law enforcement, and criminal prosecution, as well as the medical and mental health fields. All team members collaborate to investigate, prosecute, and treat victims of physical and sexual child abuse and neglect.

MDTs can be found in the Children’s Advocacy Centers (CAC) of the National Children’s Alliance, a nationwide nonprofit organization whose members include advocates, partner agencies, communities, researchers, and others dedicated to preventing child abuse and supporting its victims. Started in 1980, the Alliance now supports 939 CACs, which served more than 386,000 children throughout the country in 2021.

The Gingerbread House Children’s Advocacy Center

One such CAC is the Gingerbread House (GBH) Children’s Advocacy Center of Shreveport, Louisiana. A community-based organization, GBH works collaboratively with law enforcement, child protective services, the district attorneys’ offices, and medical and mental health professionals to investigate, prosecute, and treat cases of child abuse as well as those involving child witnesses to violent crimes.

One such CAC is the Gingerbread House (GBH) Children’s Advocacy Center of Shreveport, Louisiana. A community-based organization, GBH works collaboratively with law enforcement, child protective services, the district attorneys’ offices, and medical and mental health professionals to investigate, prosecute, and treat cases of child abuse as well as those involving child witnesses to violent crimes.

Since it was founded in 1998, GBH has helped more than 15,000 children by providing child welfare services and assisted 25 local law enforcement agencies in pursuing justice on their behalf. In 2022, nearly 1,000 children received forensic interviews through multidisciplinary investigations. Says Jessica Milan Miller, Chief Executive Officer, “The Gingerbread House is a safe haven—a soft place to land—for children who have been hurt through physical or sexual abuse. We are essential first responders in child abuse investigations.

“We have been serving for almost 25 years and have an amazing working relationship with law enforcement agencies. Using the multidisciplinary team model, we all work together in the investigation and follow-up.”

Child-oriented Forensic Interviews

Miller says, “Detectives naturally wonder, ‘What are you going to do with my investigation?’ They want legally solid interviews, but once they get into the process here, they can see the value of our forensic investigators, who are skilled at getting the facts without additionally traumatizing the child.”

GBH employs forensic interviewers who are trained in obtaining the details necessary to conduct effective and complete investigations of sexual assault, severe physical abuse, human trafficking, commercial child sexual exploitation, child pornography, and child witness of violent crimes. These interviewers are experts in child development and well versed in state laws regarding children, allowing them to provide the best nonleading and neutral approach to forensic interviews in a nonthreatening environment.

The interviews are conducted in a child-friendly room by one of GBH’s five forensic interviewers, who are experienced in talking with children about difficult subjects in an age-appropriate manner. Law enforcement detectives and child protective service workers involved with the case monitor the interview live via closed circuit television. When it’s over, two DVDs are made of the interview, and the law enforcement investigator takes the recorded statement to use as evidence and forward to the district attorney’s office for prosecution review.

The Benefits of a Multidisciplinary Team

The MDT approach minimizes the number of times a child has to be interviewed—usually to just once—and ensures that the child receives all appropriate services throughout the legal process. Working together, MDTs also ensure not only that each incident is properly investigated and responded to but also that the victim’s physical and emotional injuries are attended to by doctors and therapists. Social workers work with the families to address any issues related to the case.

This collaborative approach has additional benefits. By improving interagency communication, it increases the effectiveness of the investigation and prosecution. Each team member understands the others’ different roles, responsibilities, strengths, and weaknesses, as well as their obligation to cooperate and coordinate their efforts.

Asked how law enforcement agencies in other states should join such a team, Miller says, “The best place to start is on the website of the National Children’s Alliance. Do a search to find search the names of centers in your state.

“In Louisiana, there are 15 CACs, so every parish has access to one. Look at what is available in your state, then reach out to the CAC closest to you and see what they’re doing. Also look at your community to see if you have the resources to enable adopting their model.”

Guidance for Setting up a Child Protection MDT

She goes on, “The National Children’s Alliance can provide guidance as well as a sample interagency agreement and templates for other forms. The CACs are accredited through a rigorous process, almost like a hospital. And every five years it must be renewed, so you can be assured of the CAC’s quality.”

She goes on, “The National Children’s Alliance can provide guidance as well as a sample interagency agreement and templates for other forms. The CACs are accredited through a rigorous process, almost like a hospital. And every five years it must be renewed, so you can be assured of the CAC’s quality.”

Further guidance on setting up an MDT can be found in Law Enforcement Response to Child Abuse, a publication of the U.S. Department of Justice Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. In addition to emphasizing the need for all members of the child protection team to have clearly defined roles, the publication notes that all of them also have an obligation to appreciate what the other professionals are trying to accomplish and to understand how their activities interrelate. As an example, it states that law enforcement officers need to be concerned that their investigation could traumatize a child, and physicians and therapists need to be concerned that their treatment and evaluation techniques could hinder or damage law enforcement’s investigation.

Drawing up an interagency protocol establishing written guidelines can enable optimal collaboration from the outset. And a properly drafted agreement can also provide an appropriate action plan for each of the principal agencies responsible for abuse cases in the community.

Regularly scheduled meetings also play a role in effective collaboration. At GBH, the MDTs meet monthly to review cases in a confidential environment where information can be tracked and coordinated. Throughout the year, MDT members also benefit from professional trainings and cross-discipline learning opportunities, ensuring that all stay current with new developments in the child advocacy field.

Asked to explain how forensic interviewing and the caring collaboration of GBH’s MDT helps young victims, Miller says, “We let the children know they are not defined by what happened; just because something bad happened doesn’t make them bad. We walk along with them, and never let them feel stuck or labeled. And they’re resilient, so with help, they can heal.”

As testimony to the benefits of this approach, Steve Prator, Sheriff of Louisiana’s Caddo Parish, is quoted on the Gingerbread House’s web site as saying that GBH is “a godsend for children, families, and the entire criminal justice system.”

Faye C. Elkins

Sr. Technical Writer

COPS Office

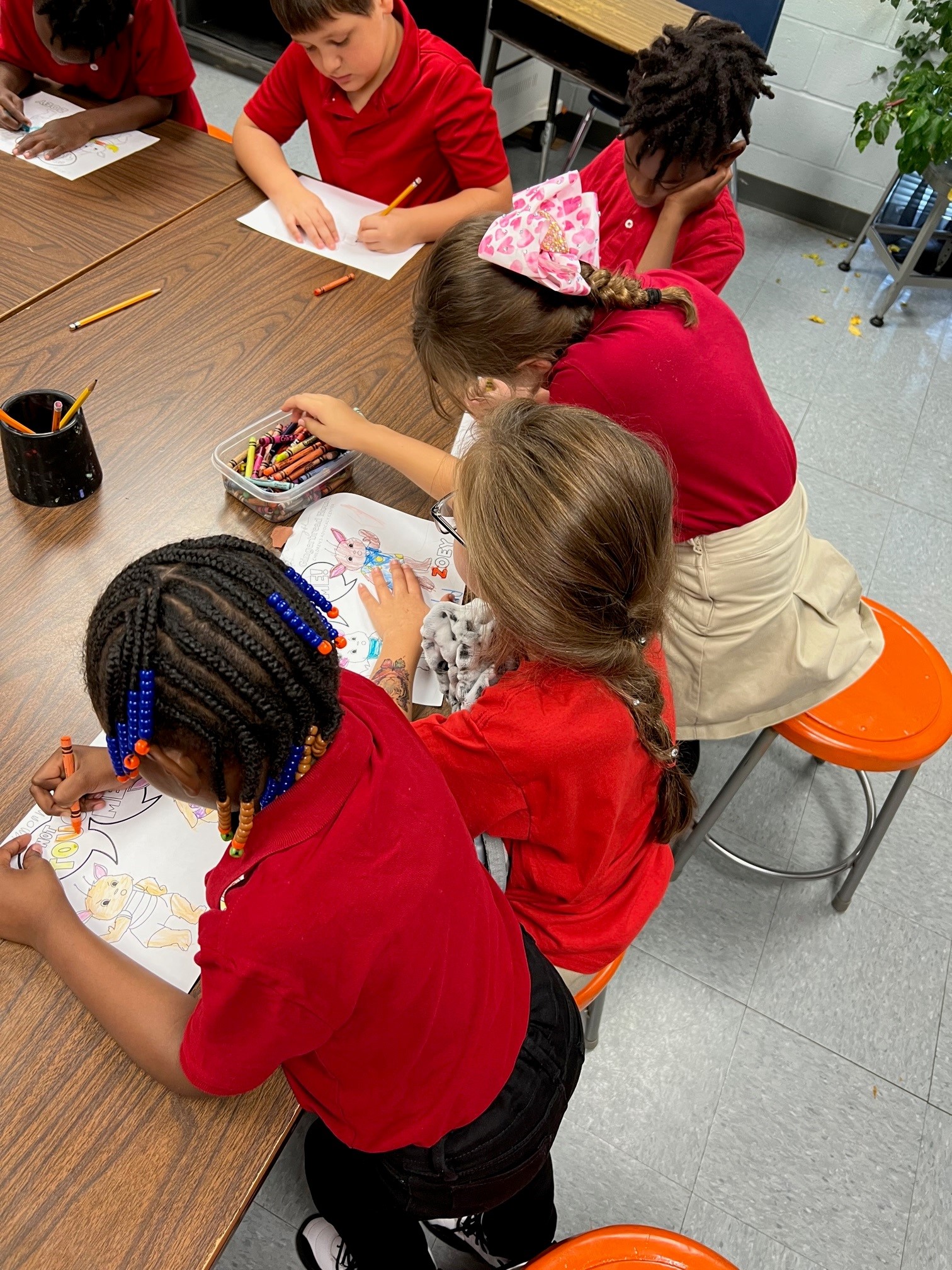

Images courtesy of the Gingerbread House Children’s Advocacy Center.

Subscribe to Email Updates

To sign up for monthly updates or to access your subscriber preferences, please enter your email address in the Subscribe box.