Contact Us

To provide feedback on the Community Policing Dispatch, e-mail the editorial board at CPDispatch@usdoj.gov.

To obtain details on COPS Office programs, publications, and resources, contact the COPS Office Response Center at 800-421-6770 or AskCopsRC@usdoj.gov

U.S. Department of Justice

Office of Community Oriented Policing Services

Washington, DC 20530

Researchers identified and described best practices for law enforcement interviewing of trafficking victims, based on the literature.

Victims of human trafficking play a key role in the investigation and prosecution of traffickers; however, the quality of the victims’ interactions with interviewers largely determines their involvement in the interview process and the information they disclose. Victims of human trafficking have characteristics, needs, and relationships with the police that are unlike those of other types of victims, law enforcement faces distinctive challenges in earning their trust and willingness to participate in the process. Little is known about the effectiveness of interviewing strategies with trafficking victims, and there is limited evidence-based or actionable guidance to strengthen interviewing practices with them. Consequently, interviewers have little information about (a) the effects of interview techniques on victim outcomes and perceptions or (b) how to minimize retraumatization.

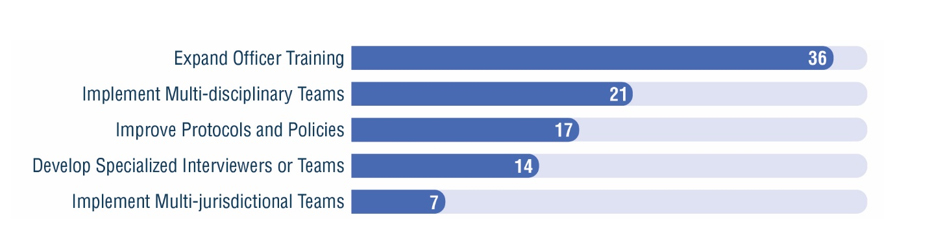

To fill this gap, independent consultants funded by the National Institute of Justice (NIJ) systematically examined the available literature on law enforcement interviews of potential human trafficking victims. Researchers synthesized relevant literature and provided a summary of interviewing practices and recommendations (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Summary of the literature’s most common recommendations for improving law enforcement interviews of human trafficking victims. The bar graph shows the number of studies in the review citing the recommendation.

Action: Addressing Victim Needs

Despite the limited body of evaluative research, law enforcement agencies can address victims’ needs and take immediate action:

- Expand officer training to improve investigative and interviewing skills when dealing with trafficking victims. A first step toward developing the specific skills needed to conduct trafficking investigations is to expand or modify current investigative interviewing training curricula to encourage rapport-based and victim-centered approaches (see also recommendation 3).

Studies noted that, despite recent attempts to expand officer training, considerable gaps still exist in training content.1 In one study, victim service providers identified a difference between training and raising awareness; many efforts to “train” officers on human trafficking are too superficial. Events that cover a wide range of information or are provided to multiple levels of an organization (e.g., executive, management, and front-line staff) may be effective at raising awareness about trafficking victimization, but they are not as effective at providing interviewers with the necessary tools and skills to identify, interview, and assist human trafficking victims.2

- Implement multidisciplinary, multijurisdictional teams. Many studies recommended developing regional task forces and cross-disciplinary teams (including both law enforcement and prosecutors) as well as incorporating victim service providers throughout the investigative process. This approach could improve case and investigative outcomes and reduce harm and retraumatization of victims. Using a multi-disciplinary approach could also enhance communication across jurisdictions and create training and information-sharing opportunities.3,4, Multiple studies touted the benefits of developing strong, long-lasting partnerships among different components of the criminal justice system and victim support services.

- Improve protocols and policies to focus on using a victim-centered approach at all stages of a criminal investigation. Adopting a victim-centered approach was the most frequently discussed recommendation for law enforcement.5,6,7, A victim-centered approach means understanding that traditional measures of criminal justice success (e.g., arrests, successful prosecutions) are secondary to a victim’s physical and psychological needs (e.g., their safety, their children’s safety, how they will support themselves, access to services, and legal protections). Law enforcement should emphasize empathy, respect, collaboration, and sensitivity in relation to the victim's rights, needs, and preferences.

- Develop specialized interviewers or teams who are actively trained and experienced in working human trafficking cases. Studies recommended that interviewers become aware of the effects that trauma may have on victim behavior (e.g., nervousness, lack of eye contact, “inappropriate” affect) and ability to recall and report information. Trauma victims may experience memory fragmentation and report inconsistencies and errors, degrading the quality of their statements. Given the effects of trauma, studies recommended that interviewers refrain from making assumptions about victims’ credibility based on nonverbal and reporting behaviors; it is common for victims to change their statements as they process their experience over time.8

- Focus on victim identification. Studies consistently described the difficulties associated with identifying human trafficking victims. Several factors contributed to these difficulties, including victims’ reluctance, unwillingness, and inability to self-identify as victims; complex dynamics between victims and traffickers; fear of negative consequences (including the possibility of deportation); involvement in criminal activity as part of being trafficked (e.g., sex work and drugs); and difficulty describing abuse.

Several studies recommended using validated screening tools for victim identification but emphasized they should be delivered in a sensitive manner. Common categories of screening questions include work and living conditions, physical and mental health, trauma, substance use, arrest history, and prior involvement with law enforcement.

There is an urgent need to develop an evidence-based, specialized, victim-centered interviewing protocol for human trafficking cases. The most frequently recommended change focuses on expanding officer training and improving the identification of potential trafficking victims. The second most common recommendation was the use of multi-disciplinary teams that involve law enforcement, service providers, and representatives from prosecutors’ offices. Many studies also recommend multi-jurisdictional teams to ensure that individuals who committed trafficking crimes and their victims can more readily be identified. Recommendations for protocol improvements typically focus on how to identify potential victims of trafficking, while policy improvements tend to focus on processes agencies should implement to ensure that victims are treated according to best practices that are victim-centered and trauma-informed.

Find More Research

See a list of publications on the NIJ Human Trafficking topic page.

About This Article

The work described in this article was supported by NIJ award number 15PNJD21F0000011, awarded to Bixal Solutions.

This article is based on the consultant report “Practices for Law Enforcement Interviews of Potential Human Trafficking Victims: A Scoping Review” (pdf, 65 pages), by Katherine Hoogesteyn, Ph.D. and Travis Taniguchi, Ph.D.

Maya Metni Pilkington

Office of Justice Programs

References

1 Amy Farrell et al., “Identifying Challenges to Improve the Investigation and Prosecution of State and Local Human Trafficking Cases,” Final report to tidhe National Institute of Justice, award number 2009-IJ-CX-0015, April 2012, NCJ 238817, https://nij.ojp.gov/library/publications/identifying-challenges-improve-investigation-and-prosecution-state-and-local-0.

2 Heather J. Clawson and Nicole Dutch, “Identifying Victims of Human Trafficking: Inherent Challenges and Promising Strategies from the Field,” Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, http://www.aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/migrated_legacy_files/42671/ib.pdf.

3 Kevin Bales and Steven Lize, “Trafficking in Persons in the United States. Croft Institute for International Studies, University of Mississippi,” Final report to the National Institute of Justice, award number 2001-IJ-CX-0027, November 2005, NCJ 238817, https://nij.ojp.gov/library/publications/trafficking-persons-united-states-final-report.

4 Jennifer Middleton and Emily Edwards, “A Five-Year Analysis of Child Trafficking in the United States: Exploring Case Characteristics and Outcomes to Inform Child Welfare System Response,” International Journal of Forensic Research 8, no. 5 (2020): 192-203, https://medcraveonline.com/FRCIJ/FRCIJ-08-00328.pdf.

5 International Centre for Migration Policy Development, “Anti-Trafficking Training for Frontline Law Enforcement Officers: Training Guide,” 2006, https://www.icmpd.org/file/download/54281/file/Anti-Trafficking%2520Training%2520for%2520Frontline%2520Law%2520Enforcement%2520Officers%2520-%2520Background%2520Reader.pdf.

6 Shireen S. Rajaram and Sriyani Tidball, “Survivors’ Voices—Complex Needs of Sex Trafficking Survivors in the Midwest,” Behavioral Medicine 44, no. 3 (2018): 189-198, https://doi.org/10.1080/08964289.2017.1399101.

7 Suzanna L. Tiapula and Melissa Millican, “Identifying the Victims of Human Trafficking,” Prosecutor: Journal of the National District Attorneys Association 42, no. 1 (2008): 34+, https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?v=2.1&it=r&sw=w&id=GALE%7CA186516778&prodId=AONE&userGroupName=anon~c468358f&aty=open-web-entry.

8 Susan E. Brandon, Simon Wells, and Colton Seale, “Science-Based Interviewing: Information Elicitation,” Journal of Investigative Psychology and Offender Profiling 15, no. 2 (2018): 133-148, https://doi.org/10.1002/jip.1496.

9 Jonathan Dickinson Dabney, “Identifying Victims of Domestic Minor Sex Trafficking in a Juvenile Custody Setting,” Masters of Science diss., Portland State University, 2011, https://www.proquest.com/criminaljusticeperiodicals/docview/884580400/abstract/EB652D6E1E72476DPQ/15.

Subscribe to Email Updates

To sign up for monthly updates or to access your subscriber preferences, please enter your email address in the Subscribe box.