Contact Us

To provide feedback on the Community Policing Dispatch, e-mail the editorial board at CPDispatch@usdoj.gov.

To obtain details on COPS Office programs, publications, and resources, contact the COPS Office Response Center at 800-421-6770 or AskCopsRC@usdoj.gov

U.S. Department of Justice

Office of Community Oriented Policing Services

Washington, DC 20530

Editor’s Note: In light of the Supreme Court’s Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta decision of June 2022, some of the ramifications of McGirt v. Oklahoma have changed to indicate the state can play a role in criminal prosecution on tribal lands if committed by non-Indians. The article below continues to provide useful historical context and law enforcement perspectives and we encourage you to read it.

Despite centuries-old treaties, the sovereignty of American tribal nations has been repeatedly challenged, both in state courts and the communities that border their lands.

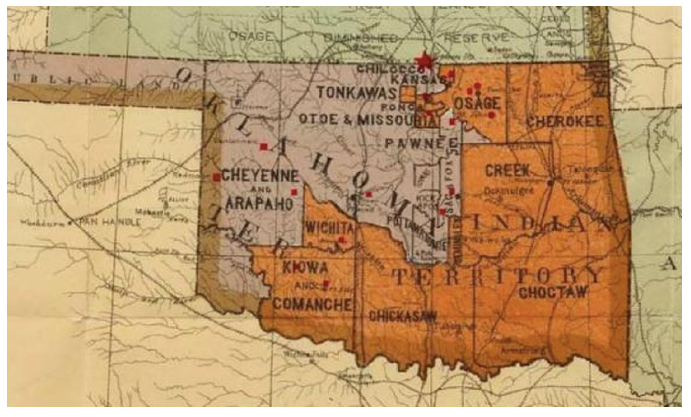

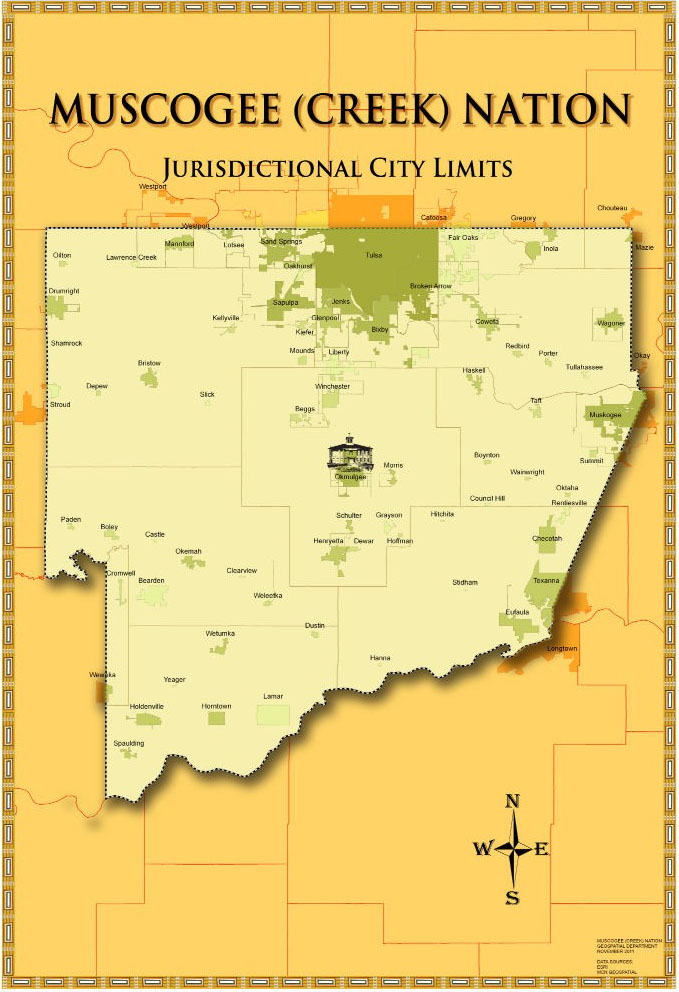

But a July 2020 landmark decision by the U.S. Supreme Court, which answered the question of which geographic areas are within the Muscogee Creek Nation’s legal jurisdiction, has not only had far-reaching effects in the tribe’s home state of Oklahoma, but also provides a precedent that can be applied to jurisdictional disputes throughout the nation.

The Supreme Court case, McGirt v. Oklahoma, was brought by Jimcy McGirt, who was convicted of serious sexual offenses by an Oklahoma state court. After unsuccessfully arguing that the state lacked jurisdiction to prosecute him because he is a member of the Seminole Nation and his crimes took place on the Muscogee Creek Nation reservation, he appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Major Crimes Act in Indian Country

The Court ruled in McGirt’s favor, stating that the tribe continued to have criminal jurisdiction over all of the land which was reserved for the Muscogee Creek Nation in an 1866 treaty with the U.S. government—including property allotted to individual tribal members and others under various laws.

In other words, the federal government—not the state—has jurisdiction over serious crime committed by Native Americans on the Muscogee Creek Nation. In light of the ruling, McGirt’s state conviction was overturned.

Under the Major Crimes Act (MCA) of 1885, major felonies such as murder, sexual abuse, and kidnapping, are typically investigated by the FBI and prosecuted by U.S. Attorneys if they are committed by Native Americans on tribal land.

Tribes have jurisdiction over Indians for misdemeanors and lower level felonies, such as minor assaults, impaired driving, user-level drug possession, and thefts. Tribal criminal jurisdiction over non-Indians is limited to certain domestic-violence-related crimes.

Benefits to Tribal Sovereignty and Criminal Justice

The McGirt decision was hailed as a triumph for tribal sovereignty by the Five Civilized Tribes, which include the Cherokee, Choctaw, Seminole, and Chickasaw, as well as the Muscogee Creek Nations, and whose combined land covers almost half of the state of Oklahoma.

The main benefit of McGirt was that tribal governments regained their right to administer justice according to their own laws and traditions. Says Mike McBride III, a lawyer at the firm of Crowe & Dunlevy and a former attorney general of the Seminole Nation, “In effect, this will be a reallocation of services, determining which sovereign entity will run criminal justice, investigation, prosecution, and confinement in a criminal case.”

“It can restore the tribes’ ability to tailor their justice systems to their unique histories, customs and culture,” he adds. “Adjudicating and resolving disputes according to their own laws, customs and traditions is very important to them.”

In fact, the approach of many tribes to criminal justice often differs from that of the federal or state governments. Most tribes emphasize rehabilitation over punishment and prefer restorative justice measures—in which the accused person must make restitution to his or her victim—to prison or harsh penalties. Furthermore, most tribes have not opted in to apply the federal death penalty on their lands.

Before this Supreme Court decision, the state of Oklahoma tried almost all criminal cases involving Native American defendants before state judges and juries. Now tribal judges and juries will decide the fates of Native Americans accused of misdemeanor and even some felony level crimes.

Law Enforcement and Prosecutors Face Challenges

Though the ruling reaffirms tribal sovereignty, it also presents challenges, including increased workloads for tribal as well as federal authorities.

According to McBride, tribal responsibility for investigation, prosecution, adjudication, and containment will require them to fund additional officers, court staff, and a jail, among other things. “We have 39 tribes in Oklahoma, and most are small and lacking in the necessary resources,” he says.

“But the smaller tribes without police forces can rely on the Bureau of Indian Affairs police for most of their law enforcement needs. And cross deputation agreements between Native and non-Native law enforcement permit the nearest peace officer to help in an emergency.”

Cross-deputation agreements can permit tribal police to investigate and arrest non-Indians for state law violations and also allow non-Indian law enforcement agencies such as local sheriffs to investigate and arrest Native Americans committing crimes that violate tribal law within their reservations.

As for Oklahoma’s Five Civilized Tribes, they are already up to the challenge, with prosecutors, courts and law enforcement personnel who will work with the U.S. Attorneys and the FBI. They also have hundreds of tribal-state cross-deputization agreements in place to address arrest powers, extradition, and 911 emergency response.

Concerns about Federal Prisons and Sentences

In addition to concerns about the effects of McGirt on tribal resources, there are questions about how Oklahoma’s federal prosecutors, who have been focused on crimes like drug trafficking and multimillion-dollar swindles, will handle a potential flood of legal cases, such as serious assaults, homicide, and child abuse, which were previously handled by Oklahoma’s district attorneys.

Says Shannon Cozzoni, Northern District of Oklahoma’s Deputy Chief, Criminal Division, Indian Country, “We’re having to triage our cases now to deal with the most serious.”

Another concern related to the McGirt decision is that the MCA can lead to over-incarceration of Indigenous people in the federal prison system. Because of federal sentencing guidelines, people convicted in federal courts might receive longer sentences than those convicted of similar crimes in state courts. And there are differences in how some offences are seen, especially drug use.

What’s more, federal prisoners are often sent to facilities far from their homes and families. As a result, some children of incarcerated parents haven’t seen them for years.

Cross Deputization and Collaboration Are Key to Success

There are a number of large and small issues to be worked out, but the Five Civilized Tribes are already working with federal prosecutors and state law enforcement. Said McBride, “The state and these tribes have a long history of cooperation. There’s nothing that can't be solved by their working together to make sure that all citizens are protected.”

And though McGirt v. Oklahoma ruled on a case involving the Muscogee Creek Nation, the decision has ramifications for other tribes and other states as well. Says McBride, “This signals that these treaties really do matter. If congress doesn’t explicitly disestablish a reservation, it still exists.”

McBride recommends that law enforcement in other states reach out to their local tribal officials, U.S. Attorneys’ Offices, and the Bureau of Indian affairs to determine if there is Indian Country in their area, and if so, exactly what the boundaries and legal status of these tribal nations are.

“Then work with your co-sovereigns and try to cross-deputize with them, the FBI, and the BIA as much as you can,” he says. “Get those agreements in place so arrests can’t be challenged later.”

There will be fewer cases for state and local law enforcement, but a need for greater coordination with tribal law enforcement agencies. “Working together, things might get a little more complicated,” says McBride, “but it can be done effectively, and it’s in everybody’s interest for it to succeed.”

Faye C. Elkins

Sr. Technical Writer

The COPS Office

For more information, please see: Policing on American Indian Reservations

Subscribe to Email Updates

To sign up for monthly updates or to access your subscriber preferences, please enter your email address in the Subscribe box.